The Price Of Stability In China

Heading into the year of 2017, the word on everyone’s lips when it came to China was stability. With Xi looking to consolidate power in the upcoming government reshuffle in November, he would need the country as stable as a rock for another 11 months, and for the last 4 months, China appeared to be pulling it off. The PBOC’s pile of FX reserves had not only held steady, but began to rise. The country posted a higher than expected GDP growth of 6.9% in Q1 (that is if you think the market cares about the GDP number). SOE industrial profits were soaring… But above all, the Yuan held steady. From the WSJ (my emphasis in bold):

“BEIJING—President Xi Jinping gathered with his economic mandarins in December for their annual strategy meeting at a heavily guarded government hotel. In closed-door sessions, say people familiar with the confab, he made clear what their mandate was for 2017: He would tolerate no wobbliness in the economy.

The communiqué coming out of the session singled out one policy objective in particular—keep the yuan stable.

What followed has been the marked acceleration of a shift in priorities at the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, toward preventing the currency from cratering above all else.“

Much has been said about the relative success the Chinese government has achieved in the first quarter of this year but there has been little said about the costs of their actions. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, and you can bet the Yuan’s recent stability did not come cheap. Since late February, financial assets in China have been selling off. The industrial commodities were the first to fall.

#IronOre futures in #China continue to plunge in night hour, down 6% following 8% drop in day trading pic.twitter.com/Q9j7OxXDOE

— YUAN TALKS (@YuanTalks) May 4, 2017

The equity market was next.

Chart Of The Week(by views): Is This The Black Sheep Among Global Equity Markets? $ASHR

Post:https://t.co/z6rifzXPX6 pic.twitter.com/Cbfo6OfYKs— Dana Lyons (@JLyonsFundMgmt) May 13, 2017

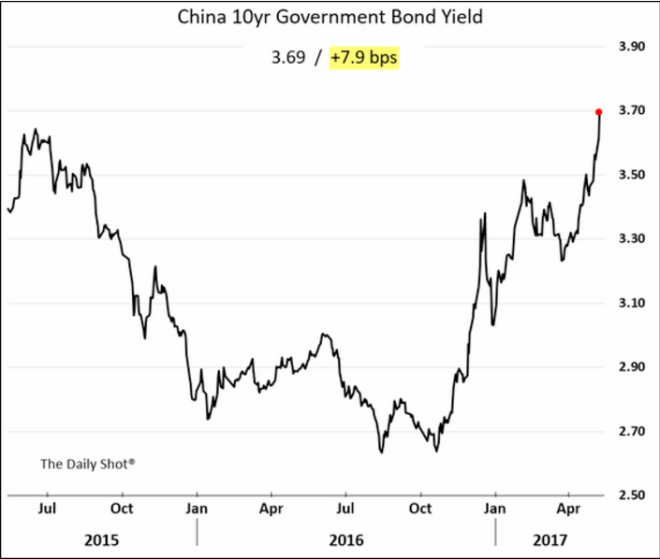

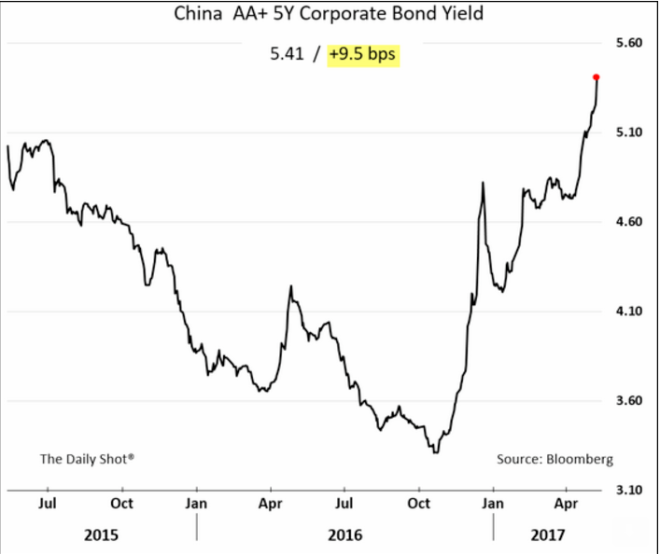

But more importantly the bond market has witnessed a dramatic sell off across the board.

The sell off in Chinese Corporate credit has been even more dramatic.

Even more serious signs of stress have begun to show up in the system.

#China's yield curve just inverted. Watching closely… https://t.co/lqURR5Eus9 pic.twitter.com/Dvdzymk8d8

— For What It's Worth (@FWIWmacro) May 14, 2017

Sharply rising interest rates threaten China’s massive shadow banking system which is “estimated” to be at $9.4T or 87% of China’s GDP. From WSJ:

“Shadow banking in China has nearly tripled in size to around 65 trillion yuan ($9.4 trillion) by the end of 2016 from five years earlier, equal to around 87% of gross domestic product, according to Moody’s Investors Service.”

I say estimated because no one, not even the Communist Party knows where all the risk is hidden. From Bloomberg (my emphasis in bold):

“Rising defaults in China are unearthing hidden debt at companies across the country.

Small firms that can’t get loans by themselves have been winning banks over by getting other companies to guarantee their borrowings. The companies making those pledges exclude them from their balance sheets, leaving creditors in the dark. Borrowers often extend the guarantees for each other, raising the risk that failures could ricochet, at a time when increasing borrowing costs have already added to strains.

China’s banking regulator has ordered checks of such cross-guaranteed loans, Caixin reported Friday. “

Essentially, the regulators have marched straight into a mine field before checking where the mines were. Only after a few blow ups did they decide to ask the mines to reveal themselves. Talk about an omnipotent top down management style you’d want to bring home to your country. In stark contrast to these warning signs, investors have continued to throw money at Emerging Markets.

EM portfolio inflows recorded the best 3-month stretch since 2014, with April marking 3rd straight month of inflows of at least $20 billion. pic.twitter.com/bFXXrNLcmm

— IIF (@IIF) May 3, 2017

Investor flows/sentiment aside, if we take a closer look at where these cross guaranteed loans are located, we find the story only gets worse as much of the shady dealing has occurred between the weaker firms in the weaker sectors of the economy.

“This debt minefield could be big. The amount of loan guarantees at privately held firms in China is equivalent to 11 percent of their equity, and at LGFVs is 18 percent, according to Citic Securities Co. The load is even heavier at weaker borrowers. About 44 percent of issuers rated lower than AA- have a ratio of more than 30 percent, according to Everbright Securities Co.“

Mal-investment is often the price paid for keeping zombie companies on life support for decades. The least healthy companies are given just enough to survive and nothing more. And there’s good reason why you shouldn’t give zombie companies more than they need… because they do really stupid things with that money.

China's zombie firms staying alive with WMP investments –

813 billion yuan in 2016 says Caixin https://t.co/iNygyns9EE pic.twitter.com/TrQTJ8AoW2— Tom Orlik (@TomOrlik) May 9, 2017

From Caixin:

“In the 12 months ending Wednesday, 9,641 publicly traded companies listed on China’s A-share market moved 887.2 billion yuan ($128.5 billion) of capital into such financial products, according to data compiled by Chinese financial information provider Wind. That was a whopping near-46% jump over the same year period ending May 10 of last year.“

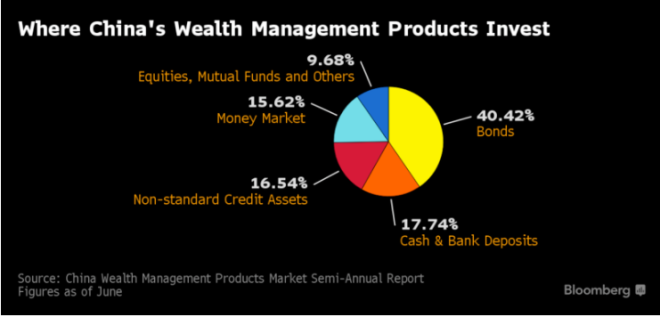

That’s right, China’s zombie firms took the “free money” the government handed out like candy back in Q1 2016 and invested it in these Ponzi Wealth Management Products. To be fair, $128.5B is just a small amount of the total outstanding WMP market which has ballooned to $4.35T or over 10% of China’s financial system in just a few short years.

Zombie companies investing in WMPs for gains is just the next step in the evolution of WMPs. From investing in the same assets to themselves, WMPs are interconnected in more ways than we can imagine.

Given WMPs are really just levered bets on other financial assets, and that every financial asset class in China is in some form of a sell off at the moment, it’s not hard to believe that the losses have begun to pile up. These losses are compounded when one WMP is invested in another. If one WMP loses money so too do the WMPs that are invested in it. So the Chinese banks, in order to survive will have to issue an accelerating rate of WMPs to paper over these losses…

Except we are seeing the exact opposite. WMP growth began to slow in March. From Bloomberg:

“Outstanding products issued by banks stood at 29.1 trillion yuan ($4.2 trillion) as of March 31, up 18.6 percent from a year earlier, according to the China Banking Regulatory Commission. The growth rate slumped from 53 percent during the same period last year, CBRC said.”

Only to slow even further in April. From Bloomberg:

“The number of wealth-management products issued by Chinese banks slumped 39 percent in April from the previous month, while trust firms distributed 35 percent fewer products, according to data compilers PY Standard and Use Trust. Sales of negotiable certificates of deposit, a popular instrument of interbank lending known as NCDs, tumbled 38 percent from a record, figures compiled by Bloomberg show.”

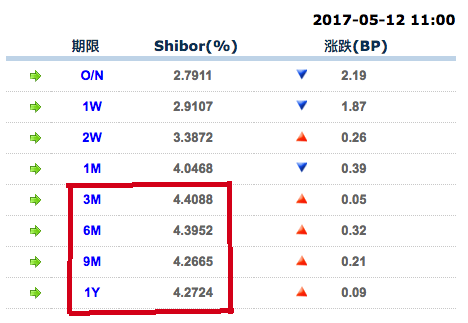

With rising losses and not enough additional funding to paper the losses the liquidity in China’s interbank market has dried up and recently like the Chinese government yield curve, inverted.

Of course it’s not just WMP issuance that has slowed dramatically, the entire shadow banking sector has tightened its lending. From Reuters:

“Trust loans, entrusted loans and undiscounted banker’s acceptances, which are common forms of shadow banking activity in China, totaled 177 billion yuan in April, down from 753.8 billion yuan in March, according to Reuters calculations based on the central bank’s data.”

The entrusted loan industry is $1.7T. Of which $500B comes from WMPs! Not only are WMPs invested in each other, but they are also loaned out to asset managers who lever up and speculate with those funds. From Bloomberg:

“When banks sell wealth-management products — popular savings vehicles that offer higher yields than deposits — the firms sometimes farm out client money to entrusted managers such as hedge funds and mutual funds. The managers invest the cash in bonds, stocks and other securities, hoping to generate enough income to cover the banks’ promised returns to WMP clients — plus some extra for themselves.

Chinese banks allocated an estimated 3.46 trillion yuan of WMP cash to such managers as of Sept. 30″

With paper wealth losses piling up and magnified by the leverage, China’s banking system is in dire need of liquidity. Unless the PBOC is going to allow a hard landing this year, we will have to see a massive amount of liquidity pumped into China’s banking system. Which brings us right back to where this all started, the Yuan’s stability.

Despite the PBOC’s dramatic tightening of monetary policy, the Yuan barely held its own against the dollar. The pattern in USD/CNY looks eerily similar to past instances prior to a weakening of the Chinese Yuan.

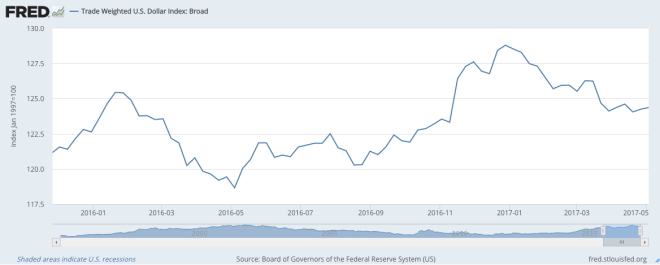

It’s worth noting that the dollar hasn’t even been particularly strong in 2017. It has fallen quite steadily against a basket of currencies since the year began.

So if the Yuan, despite dramatic tightening out of the PBOC, cannot maintain its value against a weak currency, what’s going to happen to the Yuan if the PBOC is forced to unleash a new wave of liquidity? Will CCP be able to prevent capital flight again?

I don’t think they’ll be very successful. At the same time, I recognize the futility in trying to time an event that is over a decade in the making.

Instead, imagine you are a Chinese citizen. Due to strict capital controls, you cannot get your money out of the country. Financial assets, and industrial commodities are falling in value. The government has put tighter controls on housing speculation preventing you from buying a second or third or eighth home. You are left with just a few options:

Crypto-currencies…

I feel like I might be very late to this party but… China 10 year bond yield (orange LHS) vs $btcusd (black, RHS) pic.twitter.com/TvUmVYGqWU

— Klendathu Capitalist (@KlendathuCap) May 14, 2017

And precious metals.

China’s Gold Imports Surge 65% As Production Falls 9% In Q1 https://t.co/oPpzzk2uk8

— Luis D. Garcia (@EconomicAlpha) May 2, 2017

more