How The Saudi Oil Attacks Will Impact Crude Prices

Investors on Monday digested the news of the massive drone attacks on Saudi Arabian oil infrastructure at Abqaiq and Khurais. Stocks took it… pretty well, it has to be said; the Dow slid around 0.27% as an "oil shock" that would've sent indexes tumbling hundreds of points 10 or 20 years ago rippled through the broader markets.

Oil, on the other hand, is seeing virtually unprecedented volatility. Prices for crude have jumped by as much as $10 a barrel following the disruption of around half of Saudi Arabia's daily output. Prices then lurched lower yesterday when Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman suggested oil supply will be back online by the end of September. Whether that’s possible or not is an open question.

As we'll see in a second, the ground reality is probably more complicated than that, and traders are still deeply conflicted about the big picture.

The top priority for investors right now is to get a handle on the “ceiling and floor” for crude prices.

I reached out to Mark Russano – one of the smartest guys in the global "oil patch." Mark's a former hedge fund manager at Candlewood Investment Group and South Ferry Capital. He was recently Bloomberg's principal analyst in the up- and downstream oil and gas segments.

Mark knows the sector, and he's managed money – he's the perfect source, and he sat right down with me on a call to talk about what's happening.

Here's an edited transcript of our phone conversation…

A Big "Fix" Is Needed – and Fast

Matt Warder: Thanks for talking with me, Mark. Why don't we start at the beginning, with what's really going on here in the oil market.

Mark Russano: Thanks for having me! The answer, as it turns out, is not as simple as the "5.7 million barrels per day" to which Saudi officials have alluded and the media has repeated ad nauseam.

Instead, the ultimate effect will be determined by not only the ability of Saudi Aramco to quickly repair its facilities but also by a couple of other factors. The Saudi energy ministry says production could ramp back up to 11 million barrels per day by the end of September, but even setting possible “unforeseen events” aside, it’s not clear it can attain that goal.

First and most obviously would be just how much replacement supply producers can quickly ramp up, plus how much consumers can pull from storage.

But second – and perhaps more important – is just how much of that replacement supply matches the quality of what's been removed from the market.

MW: So it's a question of quantity and quality? Walk us through that, if you would.

MR: For that, we need a quick discussion of global crude grades.

For our purposes here, there are basically just two parameters to know.

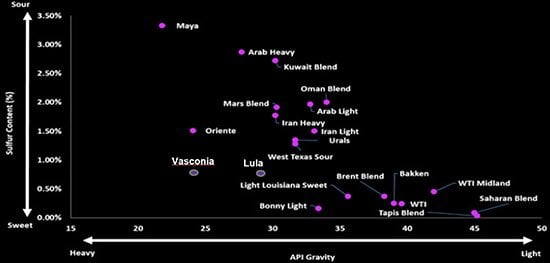

The first is "API gravity," which measures the density of liquid crude oil. A number greater than 10 means the crude floats on water, whereas a number below 10 means it sinks. Accordingly, we refer to higher API numbers as "light" and lower API numbers as "heavy."

The second parameter is the percentage of sulfur in the crude, which typically ranges from as low as 0.1% to as much as 5% by weight.

A low sulfur content is referred to as "sweet," whereas a high sulfur content is called "sour" – with the latter typically requiring some of the sulfur to be removed prior to processing in an oil refinery.

And that's it, really; every grade of crude in the entire world market can be at least loosely defined by those terms.

MW: So now we have enough of a framework to start taking a look at production, consumption, and storage. How big is the shortfall, and how can it be made up?

MR: Absolutely. Now, the Saudi complex at Abqaiq contains three separate facilities that have a total combined capacity of around 7 million barrels of oil per day.

Primarily, Abqaiq produces two separate grades – a middle-of-the-road spec called Arabian Light (32.8 API and 1.97% Sulfur) and a slightly lighter, slightly sweeter spec referred to as Arabian Extra Light (API 39.4 and 1.09% Sulfur).

Now, since most refineries are designed to take a narrow range of crude qualities, any replacement barrels will need to be pretty close in both sulfur content and in API. The easiest way to assess that is to plot every major grade on a scatter chart, like the one I've just sent you.

In this case, Arab Light is almost at the center of the chart, but plotting nearby – going from sour to sweet – is production from Kuwait, Iraq, and Dubai (Kuwait Blend); the United States (Mars Blend, from offshore drillers); Russia (Urals); Brazil (Lula); and Nigeria and Angola (Bonny Light).

In the event that the outage at Abqaiq lasts weeks or months instead of days, it's likely that any and all of these options will be called upon to offset longer-term production losses from Saudi Arabia.

It has been reported that the combination of Kuwait, Iraq, and Dubai have just under 1 million barrels per day of spare capacity that they can bring back on if need be.

In addition, slowing global demand has recently forced both Angola and Nigeria to defer shipments by a month (10 and three, respectively), which indicates they have somewhere between 300,000 and 500,000 barrels per day that could find a home almost immediately.

Meanwhile, Russia has recently doubled its export capacity to China (a key consumer of Saudi crude), and Brazil is in the process of ramping up production – though the combination of the two is unlikely to be particularly large – in the neighborhood of 500,000 to 1 million barrels per day, tops – and would take around 30 days or more to come online.

And finally, offshore drillers in the United States could bring on another 500,000 barrels per day or so in about a month, bringing the world's total available response to around 3 million barrels per day. That's a sizeable – but not complete – replacement to the Saudi outage.

MW: Okay, now what's happening on the ground in Saudi Arabia in regards to maybe getting Abqaiq back on line?

MR: That's a good question, and the answer is… it's complicated. And fluid.

Aramco's initial plan was to try and restore around 2 million barrels of output from Abqaiq by the end of Monday. Reports from the kingdom indicate it may very well have done it, but of course, there’s much, much more work to be done.

MW: What's that process going to look like?

MR: First, workers will aim to turn equipment and any built-in redundant facilities back on in a "ramp-up" fashion to ensure the integrity of the complex.

That is being done as we speak. Judging from damage shown in publicly available photos, it appears the brunt of the attack was borne by storage tankers and desulfurization units – neither of which were entirely destroyed.

That means that while full production won't be restored for some time, a partial restart will happen fairly soon – likely on the order of 1 million to 1.5 million barrels per day.

Next, the kingdom will look to ramp up any idle production – in particular, offshore assets and wells located in the so-called "neutral zone" shared with Kuwait.

Output from those assets – around 2 million barrels per day – will be routed to operational facilities and find their way to market within 30 to 60 days, meaning it's entirely possible that the country can gain back about 75% of production losses within a couple of months.

Reckoning with the "Oil Shock" and "Fear Premium"

MW: So that's the near-term picture on the ground in Saudi Arabia. How well are end-users – customers – fixed for supply? It seems to me how much or how little end-users might draw on their current stockpiles will tend to play into how oil prices behave in the short term.

MR: That's absolutely right, and it's a diverse picture. The key consumers for Arabian Light crude are China, South Korea, and Japan – and while the latter two are comparatively low on stockpiles at the moment, China appears to be relatively well supplied.

Chinese officials have already announced that Aramco will delay October shipments by up to 10 days, while September cargoes will be shipped on time – just with heavier grades of crude.

China also has the ability to release some of its Strategic Petroleum Reserve (called "SPR," estimated to be roughly 400 million barrels) if supplies become tight – a short-term measure South Korea and Japan could also take if necessary.

MW: It can't be that easy – what's the "catch?"

MR: There's always a "catch," right? So, it's completely possible Abqaiq's 5.7 million barrels per day could be fully replaced by a combination of a partial restart, idle spare capacity in the market, future ramp-ups, and drawing down stockpiles – all of those entities have competing interests, which lowers the overall likelihood of success.

Moreover – maybe more importantly – Abqaiq was supposedly protected by a missile defense system purchased from the U.S. The Saudi armed forces are thought to have around six battalions manning American-made Patriot missile batteries, along with all sorts of radars. So much so that a successful attack on it was generally regarded as a "low-probability event."

Not anymore.

In fact, I don't see anything stopping the kingdom's enemies from launching another, identical attack fairly soon.

With tensions between the Sunni-led Saudis and the Shia-led Houthis and Iranians at an all-time high and another strike possible – if not imminent – and the U.S. at least threatening to respond with military force, the global oil market is being forced to have a long, hard think about the overall security of its supply.

As such, it's likely we'll see the about half of the $7 to $8 per barrel "bump" we saw at market close on Monday to remain indefinitely. In effect, there will be a $3 to $4 per barrel "fear premium" that accounts for that perceived increase in geopolitical and military risk.

MW: What's that mean for the pricing "floor"?

MR: Well, for West Texas Intermediate, that means the absolute bottom of its price range moves up from roughly $50 to $55 per barrel, with Brent's floor rising from $56 to around $61.

And if Aramco fails to get its facilities back online for more than a month, expect the top end of those ranges to extend into the $70 or $80 per barrel range. Investors will have to contend with that.