Deflation Threat Looms As China Suffers First Population Decline Since 1949

China is battling not one but three vicious demons. The interconnected issues of insurmountable debts, deflation, and demographics threaten to sap the world's future growth potential.

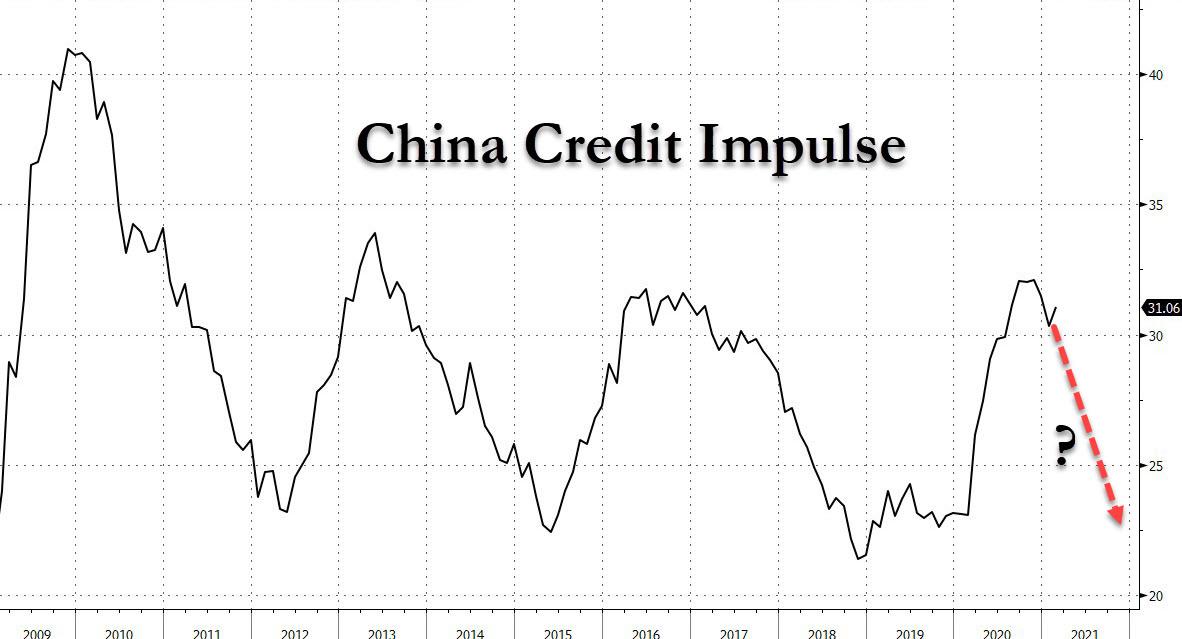

Fending off the 3 D's: debts, deflation, and demographics requires the People's Bank of China to slash borrowing costs and unleash an enormous amount of credit into the local economy to cover up the faltering demand that usually persists with demographic challenges.

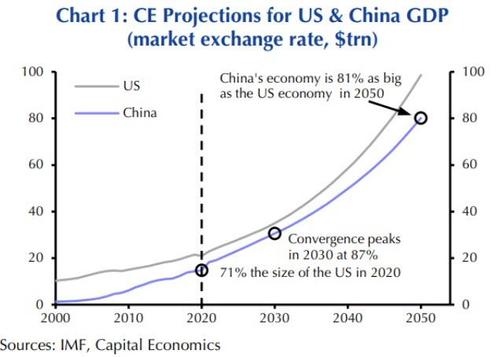

The question we should be asking is China really on the "rise," as President Xi Jinping believes: "the East is rising and the West is declining" or if the coming demographic crisis derails Xi's global takeover plans.

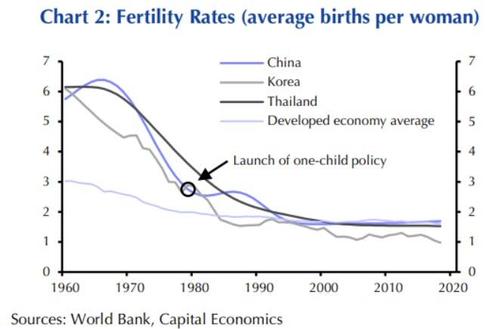

Beijing desperately attempts to recover from its decades of disastrous 'one-child policy,' which officially ended in 2015 and was replaced by the current two-child policy.

According to FT's sources, the latest Chinese census data, which was completed in December and has yet to be publicly released (the issue is reportedly so sensitive that it won’t be released until many government agencies reach a consensus on the data and its consequences), is expected to show the country's first population decline since records began in 1949.

China's total population is expected to print less than 1.4 billion, according to people familiar with the census report, and if it is reported, the peak in China's population came five years earlier than the United Nations predicted.

But, as Bloomberg notes, the trend is hardly surprising. China’s birth rate has been in decline for years and the introduction of the two-child policy in 2016 failed to make a dent. The number of newborns in 2019 fell to 14.65 million, a decrease of 580,000 from the year before. To cope with the shrinking population, a PBOC study last month urged a drastic overhaul of the policy to encourage "three or more" children per household. It called for a total lifting of any restrictions to "fully liberalize and encourage childbirth" to reverse the current four-year straight decline in births nationwide.

A key section of the 22-page document spells out:

"In order to achieve the long-term goals in 2035, China should fully liberalize and encourage childbirth, and sweep off difficulties (women face) during pregnancy, childbirth, and kindergarten and school enrollment by all means (possible)," the four central bank researchers wrote in the English language abstract.

But Mark Williams, an economist at Capital Economics, said the low birth rate has deep-rooted demographic and social causes that are difficult to reverse. After all, the decline in the fertility rate started before the one-child policy was introduced in the late 1970s, and followed a similar pattern in other Asian countries.

In any event, as the official China Daily stated in December, population "trends are irreversible."

The PBoC has a big dilemma on its hands. China today is drawing parallels between Japan in the late 1980s - just before its "lost decade," where the country experienced a decade of secular stagnation.

Firstly, demographics - if economic growth is a function of the number of workers and consumers in the economy and technological productivity, then a declining population in China would drag on the global economy.

China's next path could be down the dark road of deflation, similar to Japan, where the typical response to deteriorating demographics is a continued build-up in private debt, leading to soaring public debt.

The main lesson from Japan is that high debt levels result in structurally weak growth and anemic inflation. This would suggest the latest spurt of inflation rippling through the world is not sustainable. Future growth rates in China are expected to be much lower than what was seen pre-COVID.

Souring demographics would mean China's total social financing and M2 would need to increase to fill in the cracks of faltering demand as the population declines. According to Bloomberg's Ye Xie, a slowdown in credit growth could "start to shrink by July or August just as the Fed may lay the groundwork for its own tapering." This would signal deflation is ahead.

Besides the 3 D's: debts, deflation, and demographics, a population decline will also dent China's global image.

Huang Wenzheng, a fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, a Beijing-based think-tank, said, "census results will have a huge impact on how the Chinese people see their country and how various government departments work."

Wenzheng continued: "They need to be handled very carefully."

The Chinese take great pride in being part of the world's most populous state, but the narrative could begin to shift when the data is released.

Wenzheng said the possibility of the first population decline in seven decades could push forward China's looming demographic crisis:

"The pace and scale of China's demographic crisis are faster and bigger than we imagined," he said.

"That could have a disastrous impact on the country."

A shrinking population could have profound economic implications.

First, by Williams’s calculation, the demographic headwind means China may never be able to catch up with the U.S. as the world’s largest economy.

Secondly, an older population would put extra strain on the underfunded pension system.

A separate PBOC report last month estimated that a shrinking labor force is likely to lower China’s potential GDP growth to 5.1% by 2025, from an expected 5.7% this year. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that China’s 10-year bond yields peaked in 2013, the same year that the country’s working-age population started to fall.

Here’s a look at potential GDP growth and the three-year average of 10-year yields.

A 'deflationary' mindset and Japanification are the words that come to mind.