Factor Timing Is Tempting

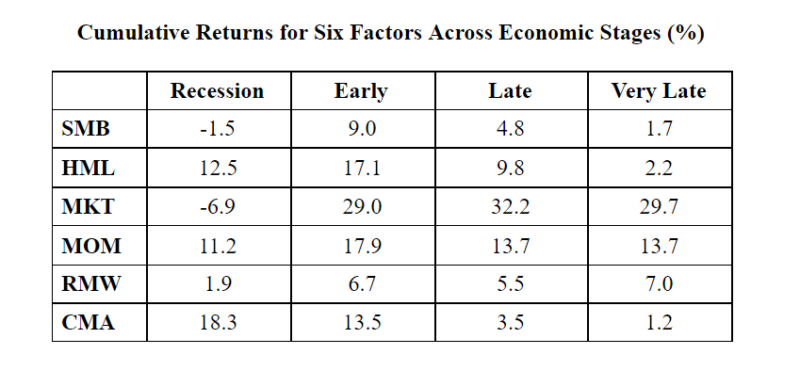

Academic research has found that factor premiums are both time-varying and dependent on the economic cycle. For example, Arnav Sheth, and Tee Lim, authors of the December 2017 study “Fama-French Factors and Business Cycles,” examined the behavior of six Fama-French factors—market beta (MKT), size (SMB), value (HML), momentum (MOM), investment (CMA) and profitability (RMW)—across business cycles, splitting them into four separate stages: recession, early-stage recovery, late-stage recovery, and very late-stage recovery. Their data, including the results shown in the following table, covered the period April 1953 through September 2015.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

As you can see, factor premiums vary and are regime-dependent. That, of course, makes timing them tempting. However, in their study “Contrarian Factor Timing Is Deceptively Difficult,” which appeared in the 2017 special issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management, Cliff Asness, Swati Chandra, Antti Ilmanen, and Ronen Israel found “lackluster results” when they investigated the impact of value timing—whether dynamic allocations can improve the performance of a diversified multi-style portfolio. They found that “strategic diversification turns out to be a tough benchmark to beat.” They added: “Tactical value timing can reduce diversification and detract from the performance of a multi-style strategy that already includes value.” They also found that contrarian value timing of factors, while tempting, is generally a weak addition for long-term investors holding well-diversified factors including value, and specifically, it does not send a strong signal even when valuations are stretched.

Providing further evidence of the difficulty of timing factor premiums is the August 2018 study “Factor Exposure Variation and Mutual Fund Performance.” The authors, Manuel Ammann, Sebastian Fischer, and Florian Weigert, examined whether actively managed mutual funds were successful at timing factor premiums (net of fees) over the period late 2000 through 2016. They found that while factor-timing activity is persistent, risk factor timing is associated with future fund underperformance. For example, a portfolio of the 20 percent of funds with the highest timing indicator underperformed a portfolio of the 20 percent of funds with the lowest timing indicator by a risk-adjusted 134 basis points per year with statistical significance at the 1 percent confidence level (t-stat: 3.3). Summarizing their results, Ammann, Fischer, and Weigert concluded:

“Our results do not support the hypothesis that deviations in risk factor exposures are a signal of skill and we recommend that investors should resist the temptation to invest in funds that intentionally or coincidentally vary their exposure to risk factors over time.”

Michael Aked of Research Affiliates took another look at the issue in his April 2021 study, “Factor Timing: Keep It Simple.” He evaluated three factor-timing strategies—a factor’s historical return, the economic stage, and a factor’s discount and momentum—using only data that was available at the time. A factor portfolio’s discount was calculated as its current valuation (using the relationship of price to various fundamental measures of the component equities) relative to its average historical valuation. A factor’s momentum was the performance of the factor over the previous 12 months.

In each case, the strategy was constructed out of sample using data only available at the time of the specific sample period. He examined eight factors: market, value, investment, size, illiquidity, profitability, low beta, and momentum) across six regions (Australia, United States, Europe, United Kingdom, Japan, and the emerging markets). Data for the U.S. began in May 1969, for Europe in April 1996, for Australia in May 2001, for Japan in October 2001, for the U.K. in December 2001 and for emerging markets in May 2003. His findings led him to conclude:

- The strategy of using a factor’s historical performance as a guide to the future is nearly worthless.

- Although a factor’s return changes throughout the business cycle, the ability to predict economic regimes and alter factor allocations accordingly produces less successful results despite being intuitively pleasing.

- Employing a factor’s discount and momentum was the most effective tool for determining how to vary a factor’s exposure through time.

Research Affiliates Disclosures

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

The finding that timing based on the state of the economy does not produce successful results should not be surprising, as the markets are forward-looking. Thus, whatever is known about the economy is already incorporated into security prices. The finding that factor discounts and momentum are the most effective tools also should not be a surprise. The reason is that this has already been well documented in the literature. For example, the authors of the 2019 paper “Factor Momentum Everywhere,” the 2020 paper “Factor Momentum and the Momentum Factor,” and the 2021 paper “Momentum? What Momentum?” found that momentum in individual stock returns emanates from momentum in factor returns—a factor’s prior returns are informative about its future returns. And the authors of the November 2019 study “Value Return Predictability Across Asset Classes and Commonalities in Risk Premia” found that valuation spreads do provide information on future returns.

They explained:

“Returns to value strategies in individual equities, industries, commodities, currencies, global government bonds, and global stock indexes are predictable in the time series by their respective value spreads.”

Further evidence on valuation spreads was provided by Thiago de Oliveira Souza, author of the December 2018 study “Macro-Finance and Factor Timing: Time-Varying Factor Risk and Price of Risk Premiums.” He found that increases in the cross-sectional book-to-market spreads significantly forecast increases in one-month-ahead premiums for all except the profitability factor. Souza’s findings were consistent with those of Adam Zaremba and Mehmet Umutlu, authors of the March 2019 study “Strategies Can Be Expensive Too! The Value Spread and Asset Allocation in Global Equity Markets,” who found that the value spread is a powerful and robust predictor of strategy returns. Aked did not cite any of these papers.

For value investors, the above findings are good news, as the relatively poor performance of value stocks in the U.S. over the past decade has led to a dramatic widening of the book-to-market spread between value and growth stocks, 1with the spread now much wider than its historical average and much wider than it was when Eugene Fama and Kenneth French published their famous study “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns” in 1992 (they had found a large value premium). In addition, given value’s outperformance since September 2020, it also has favorable momentum on its side. The evidence suggests that if you are going to try to time your exposure to factors, you should be very cautious and, to quote AQR’s Cliff Asness, only “sin a little” because the data is so “noisy”—factor volatility is much greater than factor premium.

Disclaimer: Performance figures contained herein are hypothetical, unaudited and prepared by Alpha Architect, LLC; hypothetical results are intended for illustrative purposes only. Past ...

more