Tech Is Not Inherently Risky In A Portfolio - Just Different

Technology equities (FDN) (XLK) are often seen as an inherently higher-risk asset class, whether compared to non-equities or even among different stock sectors as well. However, technology investing is not inherently more risky than any other sector but rather just different, as the technology sector's business life cycle for its companies and securities has unique attributes that can be misunderstood as just "risk."

In order to properly invest in technology, one needs to understand how technology companies come to be, grow, and taper off. That understanding can avoid investing in overvalued bubbles while helping in perhaps finding the next Apple (AAPL) or Google (GOOG, GOOGL).

(Source: Thomson Reuters)

Tech Isn't "Risky" Per Se, It's Just Different

"Technology Stocks Prove Why They Are Risky" is the headline of an April 2000 Wall Street Journal article I'm looking at. At the time, there had been massive overcrowding and demand into technology stocks that created what we now look back and call the "tech bubble."

Back then, the general market public and even the "smart money" did not fully understand how to best value technology companies, given how quickly the sector's fundamentals changed and what they saw as the potential of currently-unprofitable and small companies to someday grow to Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) levels.

Nowadays, valuations are much more controlled and almost 'too' informed. Technology companies are very carefully evaluated by the market not only when they are public equities but also even at their private funding stage, with the venture capital process a legendary struggle for its ups, downs, and general rugged difficulty.

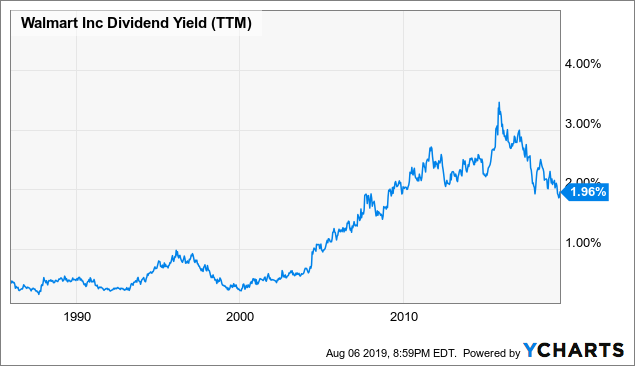

Given current broad technological trends, almost every "tech" company has a growth proposition that other industries may not necessarily have. For example, a blue-chip company like Walmart (WMT) may experience growth even now, but in the past few decades, it has reached a relatively stable state in the business life cycle and settled on its business model quite clearly.

Becoming a business that simply operates and churns out its expected earnings, it has matured into a steady dividend-payer, although even it experiences growth and decline changes.

Data by YCharts

Technology (VGT), on the other hand, has a much longer and varied life-cycle. When technology companies begin as small venture-funded enterprises, they are almost always extremely unprofitable and "burn" cash while they follow their designated business plan in achieving their initial levels of market testing, products, and establish their business model.

After raising increasing series of venture capital, many will then go public (although there are some recent changes to that trend for a variety of reasons).

Once public, however, they are not mature but often still rapidly growing and experimenting, but now usually at a level where they can at least sustain themselves without the massive raising of capital required when they were a private company.

It would seem ludicrous for a public company to suddenly in one event issue more capital than total capital it currently has raised, which is why it's done as a private company.

It is worth noting that a tech company's "maturation" stage is not necessarily its age in raw years, but rather how far it has moved along the tech development timeline from experimentation to scaling to then continued innovation. Some companies can achieve this quickly, like Facebook (FB), while others take decades to find their spot, like Nvidia (NVDA).

Nonetheless, tech companies are constantly experimenting and pushing forward in R&D in a way other sectors do not face the same competitive pressures for. This is due to the ease of entry to the sector and the current constant secular trends towards advancement. Even a company the size of Apple, Amazon (AMZN), or Microsoft is still facing constant need to innovate, even if it begins to take on mature-company characteristics.

While other mega-cap companies like JPMorgan (JPM) in financial services, Exxon Mobil (XOM) in energy, Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) in pharmaceuticals, and Walmart in retail, of course, still face innovative pressures at times, these are not constant and inherent.

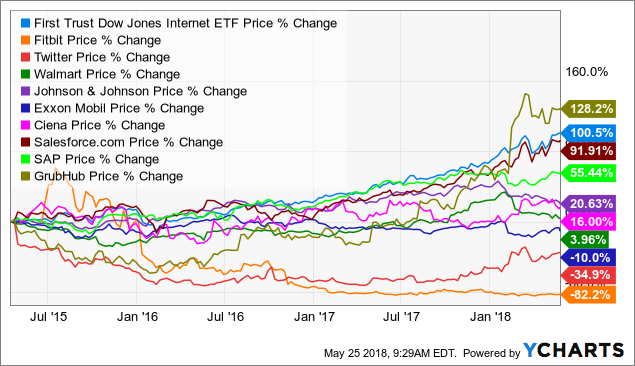

FDN data by YCharts

(Figure: Several Blue Chip Companies With Some Early And Medium-Stage Tech Companies. As shown, volatility and outcomes vary far greater for these early and medium stage companies than for the Blue Chip giants).

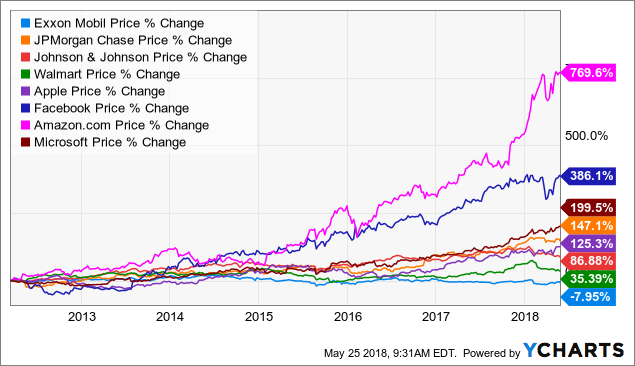

XOM data by YCharts

(The same even goes for "mature" tech companies)

OK, That Makes Sense, But How Does It Fit Into My Portfolio?

Essentially, the takeaway from the above explanation is that it's not really a question of "how much tech" but rather the "mix" and "kinds" of tech in your portfolio.

The risk-reward profile of an individual company is different from how it affects the portfolio, as in the portfolio it's about how it interacts with the rest of the assets rather than just its own nature.

Having a large batch of still relatively early-stage public tech companies, like Chegg (CHGG), and other such companies, means your portfolio will be exposed to a higher-level of volatility, risk, and uncertainty due to the inherent nature of these early-stage companies. There could also be potential above-market gains, but there are also great risks. While the overwhelming majority of startups fail, even as public tech companies can and still do fail.

In contrast, medium-stage companies like Nvidia that combine a relatively stable business model with growth aspects offer a more measured risk-reward profile within the portfolio beyond their own individual company's risk-reward profile.

Mature tech companies such as Facebook and Apple offer even lower of a risk-reward profile.

In tech, I believe the right center is around medium-stage public tech companies followed by a strong dash of mature tech companies, and then a smattering of early-stage tech companies.

For example, 45% in medium-stage companies, 40% in mature tech companies, and 15% in early-stage public tech companies create a portfolio mix that adds the potential mega-boom of even still these early-stage tech companies with lowered risk.

In contrast, a heavy allocation towards early-stage companies would create a much more "techy" boom-bust portfolio with far greater exposure to early stage companies' 'startup' volatility features they still retain at that stage.

As shown, it is less about "how much tech" in one's portfolio but rather it is really about "what kind of tech and how it is distributed."

Disclaimer: These are only my opinions and do not constitute investment advice.