Goldman Sees SPAC Frenzy Unleashing $300 Billion In Takeovers Next Year

One of the remarkable stories of 2020, one which has sparked many comparisons to 2007 just before the credit/housing bubble popped, has been the record surge of blank-check, or SPAC, issuance where investors - at a loss what to invest in - hand their money to a marquee investor who promises to find an appropriate investment over a given period of time or refund the money.

By way of background, a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a "blank-check" company formed with the intention of acquiring or merging with another company. The SPAC needs to complete an acquisition within two years or the capital raised must be returned to investors. In a typical SPAC structure, the sponsor raises initial capital by issuing units consisting of 1 share and ½ or ⅓ of a warrant. The shares are generally priced at $10 and the warrants are typically struck 15% out of the money ($11.50) with a 5-year term and an $18 forced exercise.

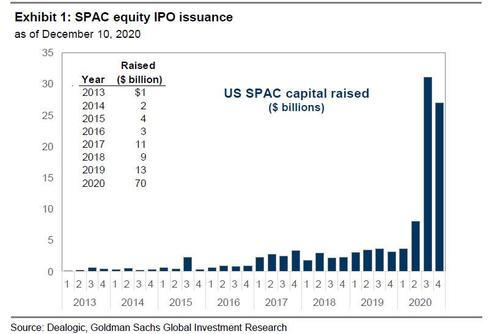

To quantify the SPAC bubble, a record $70 billion has been raised in 206 initial public offerings by blank-check firms in the first 11 months of the year. Looking at this unprecedented flood into SPACs, some wondered if the good times may be ending: in an interview with Bloomberg last month, Olympia McNerney, Goldman's head of U.S. special purpose acquisition companies, described the U.S. SPAC market as being "perhaps too frenzied" and predicted volumes will become more "rational: as fund managers deal with what she described as indigestion.

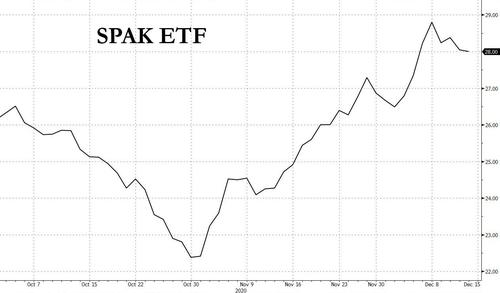

"There has been a very meaningful uptick in SPAC issuance and we expect the market to be more selective going forward," said McNerney. One of the reasons why the SPAC euphoria is expected to ease is that as investors allocate more capital to SPACs, some investors have hit internal limits governing their exposure to blank-check firms. But a far more tangible reason why the SPAC froth is likely peaking is also the simplest one: SPACs are no longer a get rich quick scheme: as recently as one month ago, 60% of October’s listings were trading below their offer price, the data show.

And although the recently launched SPAC ETF whose ticker is appropriately SPAK, slumped nearly 15% in following weeks, it has since more than rebounded hitting an all-time high last week.

(Click on image to enlarge)

And since narrative follows price, just one month after one Goldman banker warned about a SPAC bubble, another came out of the weekend to declare 2020 as the year of the SPAC.

In his Weekly Kickstart note, Goldman chief equity strategist David Kostin writes that In history books, the year 2020 will forever be known for the deadly pandemic, but from a capital markets perspective, this year will undoubtedly be known as the year of the SPAC.

Here are some details: SPAC IPO capital raising in 2020 totals a record $70 billion, a stunning five-fold increase from last year’s record high that was itself up 44% from 2018. The 206 SPAC IPOs completed this year account for 52% of the record $124 billion of total US IPO capital raised YTD across 356 transactions. SPAC acquisition announcements and deal closures also hit record highs this year. 82 SPACs representing $28 billion in IPO capital have announced M&A targets this year while 36 SPACs have closed de-SPAC acquisitions totaling $51 billion in enterprise value.

(Click on image to enlarge)

In Goldman's view, there are three reasons why 2020 has been the year of the SPAC:

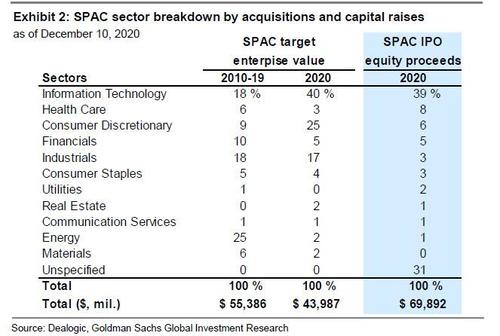

- SPAC sponsors shifted their focus from Value to Growth both in terms of completed acquisitions and new capital raising. Between 2010 and 2019, 53% of SPAC acquisitions were in the Industrials, Financials, and Energy sectors while 33% were in Info Tech and Health Care. In contrast, 68% of the de-SPACs completed in 2020 were in the fast-growing Info Tech, Consumer Discretionary, and Health Care (mostly in BioPharma) sectors while just 24% were in Industrials, Financials, and Energy. Investors are firmly in a growth mindset and SPAC sponsors targeting purchases in growth industries have had success raising capital. Fully 53% of 2020 SPAC IPOs are seeking mergers in Tech, Consumer Discretionary, or Health Care.

(Click on image to enlarge)

- The acceleration in retail trading activity has increased investor appetite for non-traditional and early-stage businesses. SPACs offer an alternative route to the public markets for firms, including those that are early-stage or in businesses that lack many publically-traded comparables such as green tech, sports betting or cannabis. Lockdowns associated with the pandemic have prompted a surge in retail trading and demand for highly-volatile shares in firms with perceived hyper-growth prospects. Anecdotal evidence of heavy retail trading coincided with the de-SPAC purchases of electric vehicle and sports betting firms (e.g. FSR, DKNG).

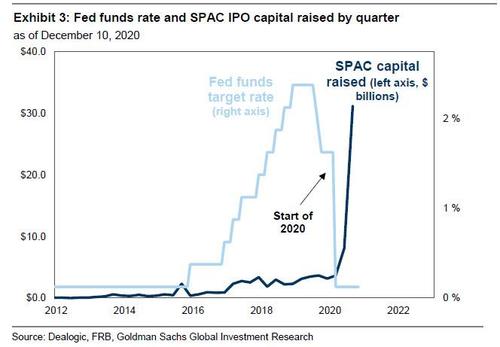

- SPACs have low opportunity cost for investors when policy rates are near zero. Cash yields next to nothing and under the Fed’s average inflation targeting (AIT) regime, a hike is unlikely during the next three years (the Fed will likely be on hold until 2024). Investors in a SPAC receive a de minimis yield while waiting for the sponsor to identify a potential target and then have a put option to redeem their shares if they do not like the potential acquisition. Of course, there is an opportunity cost of not owning equities given the 16% YTD return of the S&P 500 and our forecast of a 16% return next year. But SPACs can be a cash substitute when fed funds are at the lower bound. The focus on growth industries also means that SPACs are long duration assets that benefit from low long-term interest rates.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Clearly ignoring what his colleague Olympia McNerney said in November, Kostin this predicts that a high level of SPAC activity will continue into 2021 because, "simply put, the state of play outlined above is likely to remain in place." In other words, the warning of a frenzy has been completely forgotten (for now), and there is a reason for that: new SPAC issuance has only accelerated in 2H as 53% of the capital raised YTD has taken place since Labor Day. The most recent wave of issuance has broadened the universe of SPAC sponsors and lent institutional credibility to the SPAC process.

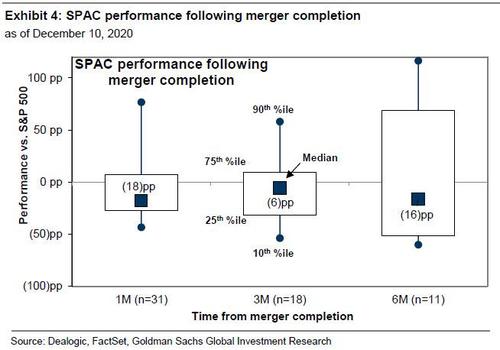

That said, and as we cautioned one month ago, weak returns represent one headwind to future SPAC issuance. Of the de-SPACs completed in 2020, the post-acquisition median 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month excess returns relative to the S&P 500 index have been -18 pp, -6 pp, and -16 pp, respectively.

(Click on image to enlarge)

If such weak returns persist, even Kostin concedes that "investor appetite for new SPACs may wane." Worse, a distribution with poor median returns and a long right tail is consistent with the SPAC return profile as Goldman discussed in July and in its 2019 report which we presented to readers previously.

One factor that determines the performance of a SPAC is the presence (or absence) of supplemental equity. Consider that most SPAC acquisitions completed during 2020 have utilized supplemental equity financings through private investments in public equity (PIPEs) or private placements. Goldman's review of company filings found that 30 of the 36 SPAC purchases completed during 2020 raised PIPEs or private placements totaling $8.4 billion concurrent with the deal closure. These 36 SPACs had original IPO proceeds totaling $10.3 billion. The use of PIPEs or private placements allowed SPAC sponsors to nearly double their cash buying power before issuing any debt.

As Kostin explains, this ability of a SPAC to raise additional capital through a PIPE or privateplacement at the time of a deal closing sends an important signal to investors. SPACs without PIPEs or private placements have dramatically underperformed in 2020. All six SPACs that did not raise incremental capital in conjunction with their mergers have posted negative returns relative to the S&P 500 from deal closure to today (an average of -42 pp vs. the S&P 500). The median return of the four SPACs without a PIPE lagged the median SPAC with a PIPE by 27 pp (-30% vs. -3%) during the three months following deal closure. When non-PIPE SPACs are excluded, the remaining 30 SPACs with PIPES posted median 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month excess returns following their mergers of -4 pp, +1 pp and +21 pp, respectively.

But the key message from Goldman's follow-up analysis is that as of this moment, the $61 billion in equity IPO proceeds raised by 205 SPACs is currently searching for acquisition targets. Based on their 24-month post-IPO expiration dates, these SPACs will need to acquire a target in 2021 or 2022, nearly equal to the total enterprise value of SPAC deal closures during the last decade. If this year’s 5x ratio of SPAC equity capital to target M&A enterprise value persists, the aggregate enterprise value of these future takeover targets would be $300 billion.

Disclaimer: Copyright ©2009-2020 ZeroHedge.com/ABC Media, LTD; All Rights Reserved. Zero Hedge is intended for Mature Audiences. Familiarize yourself with our legal and use policies every time ...

more