Prebuttal: Fiscal Policy Can Be Effective

In my mind, absent a shooting war, the economy is headed for a slowdown, if not a recession. I am confident that, should the administration or anybody else propose countercyclical fiscal policy, a set of the usual suspects will deny the efficacy of discretionary policy. Hence,a prebuttal is called for.

A Typical Skeptic’s View

Here’s a quote from an article the last time the fiscal debate raged, in 2010. From Brian Riedl’s The fatal flaw of Keynesian stimulus (Washington Times):

Last week, the Congressional Budget Office released a report claiming that the $814 billion “stimulus” has added 3.4 million net jobs.

Such implausible analysis does not come from actually observing the post-stimulus economy. Rather, it comes from Keynesian economic models that have been programmed to conclude that government spending injects new dollars into the economy, thereby increasing demand and spurring economic growth. In other words, these models are programmed to conclude that stimulus spending always creates jobs and growth, no matter how the economy actually performs.

Well, not quite. As I described in this post, there are a variety of ways in which multipliers are obtained. Oftentimes, the impacts are estimated either directly or indirectly, by estimating the marginal propensity to consume. The article continues:

But there is one problem with the government stimulus theory: No one asks where Congress got the money it spends.

Congress does not have a vault of money waiting to be distributed. Every dollar Congress injects into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed out of the economy. No new spending power is created. It is merely redistributed from one group of people to another.

It is intuitive that government spending financed by taxes merely redistributes existing dollars. Yet spending financed by borrowing also redistributes existing dollars today. The fact that borrowed dollars (unlike taxes) will be repaid some years later does not change that.

Here, I think the author, Mr. Riedl, is invoking Ricardian Equivalence, despite the fact that there is no empirical evidence, to my knowledge, that validates pure Ricardian Equivalence (actually, Ricardian equivalence wouldn’t necessary hold for government spending on goods and services, anyway). Now, at this juncture, I thought that he might be invoking a real business cycle model, or an older, nonstochastic version of the RBC, namely a flex price Classical model. But then the next paragraph reads:

Some believe stimulus spending is the mechanism by which the Federal Reserve injects new dollars into the economy. Yet the Fed could run the printing press and then inject those dollars into the economy by buying existing bonds (with mostly inflationary results). It doesn’t need an expensive stimulus bill to conduct monetary policy.

Accepting that the Fed can stimulate via monetary policy then implies either (1) sticky prices so an expansionary monetary policy can affect the real interest rate, or (2) a financial accelerator model such that collateral constraints or some other financial rigidity holds. In the latter case, it seems prima facie that Ricardian Equivalance cannot hold.

Next, I was thrown for a loop, because Mr. Riedl seems to conflate real saving and the monetary multiplier. He argues that government deficits can only be financed by foreign saving, private saving and “idle saving”. This he describes thus:

Idle savings. The only government spending that truly increases current purchasing is the amount that would have otherwise sat idle in safes and mattresses. Those are the only dollars not already circulating through the economy as consumption, or through the financial markets as investment spending.

Idle savings are rare. People and businesses generally invest or bank their savings, where the financial markets transfer them to other spenders. Banks that receive savings either lend them out to a spender, or (when afraid to loan) invest them conservatively to earn some interest. They are not hoarding customer deposits in massive vaults (beyond the required cash reserves).

This is an odd conflation of saving, measured as a flow, and financial assets. But lets take the equation at face value, there is an incredibly counterfactual observation that there no reserves are being held in excess of required cash reserves. According to the St. Louis Fed,excess reserves are now approximately $1 trillion dollars. Well, no need for facts to get in the way of a good polemic.

Mr. Riedl’s main point is:

All government stimulus spending requires first borrowing dollars that would have otherwise been applied elsewhere in the economy. The only exception is money borrowed from “idle savings,” which for reasons described above likely constitute a minuscule portion of the $814 billion stimulus.

As I’ve mentioned here and elsewhere, this is true in a full employment model. (I’m working off of textbook models; move to coordination models, or allow monopolistic power, and you have lots of other inefficiencies arising).

Mr. Riedl concludes:

Economic growth requires raising worker productivity to create more goods and services. Government stimulus spending represents a naive “magic wand” attempt to create purchasing power and wealth out of thin air.

No wonder the unemployment rate remains high.

Well, if we’re in a Classical world, then there is no involuntary unemployment. If we’re in a New Classical world, then whatever involuntary unemployment exists is not systematic. If there is involuntary unemployment, then there are resources that are not being utilized, and putting them to use naturally raises productivity (remember labor productivity is defined as output per man hour).

Empirical Evidence on the Fiscal Multipliers (from Peer Reviewed Publications, not Heritage Foundation Issue Briefs)

Instead of polemics, or reasoning from accounting identities, I’m going to appeal to empirical evidence. From my entry in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics:

Lessons from Recent Fiscal Experiment: TCJA and BBA

Since 2010, we’ve accumulated some additional observations on fiscal policy efficacy, in the form of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the Bipartisan Budget Agreement, both of which substantially increased fiscal stimulus, exactly at a time when the economy was arguably close to full employment.

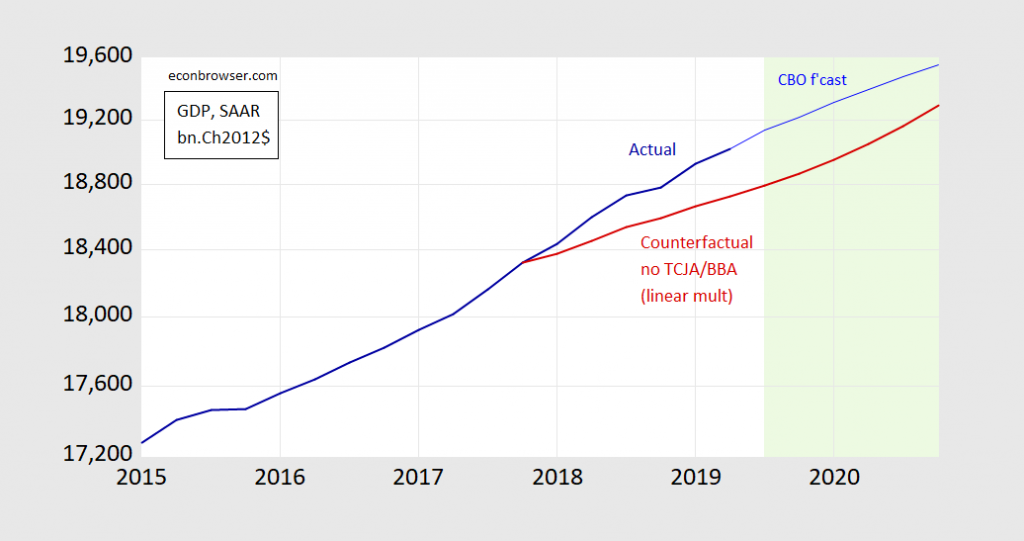

If multipliers are invariant to business cycle conditions, then conventional estimates suggests that in the absence of the fiscal stimulus, GDP growth would have decelerated. I show the counterfactual below, using estimated impacts from Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018).

Figure 1: Real GDP as reported (dark blue), GDP as implied by CBO Jan. 2019 forecasted growth (blue), and counterfactual GDP under no TCJA/BBA (red) with linear multipliers; annual output difference interpolated using quadratic fit. Light green is forecast period. Source: BEA, CBO (January 2019), and Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018), and author’s calculations.

This counterfactual seems implausible given the pre-TCJA/BBA trajectory of the economy. But perhaps this finding explains the mystery of the small impetus to GDP growth given by the Trump tax cut/spending increase. As noted in my survey:

[1] Auerbach and Gorodnichenko use a smooth transition threshold where the threshold is selected a priori. Fazzari et al. estimate a discrete threshold.

[2] Quantification of long term impacts of depressed activity on potential GDP can be found in CBO (2012b).

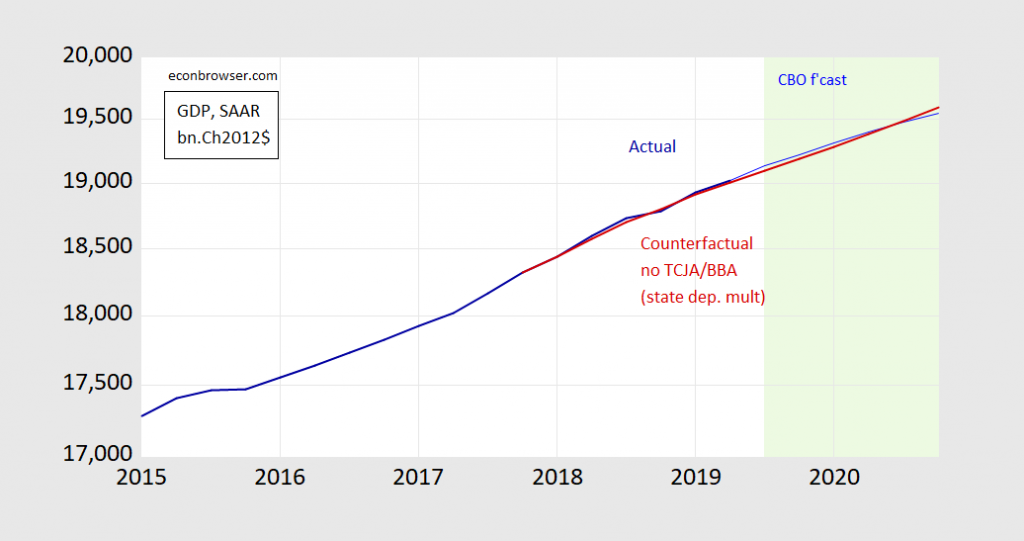

In other words, state dependent multipliers when near full employment are smaller. Using the estimates from Cohen-Setton and Gornostay, one finds that for the trillions of dollars worth of fiscal stimulus, we got precious little.

Figure 2: Real GDP as reported (dark blue), GDP as implied by CBO Jan. 2019 forecasted growth (blue), and counterfactual GDP under no TCJA/BBA with state dependent multipliers (red); annual output difference interpolated using quadratic fit. Light green is forecast period. Source: BEA, CBO (January 2019), and Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018), and author’s calculations.

Conclusion

Let’s hope we don’t go through the next recession debating in the same way whether fiscal policy can affect GDP, particularly during periods of economic slack and accommodative monetary policy (e.g., Fama, Mulligan, etc.).

Disclosure: None.