Pis Aller: We’ll Be Forced To Use Last Resorts Again In Dealing With The Next Economic Crisis

Many years ago I was involved in an oil well blowout.It started for me when I received a frantic call from one of my staff geologists that the well we were drilling had blown out and everyone had evacuated the drilling location.I quickly drove 75 miles out to the northeast of Denver to see what was going on at the well.As I drove I turned things over in my mind, but I couldn’t figure out how it could have happened.I was perplexed because we were at a total depth that was still about 1400 feet above the nearest oil and gas productive zone in that area of Colorado. Anyway, when I got there I sent my staff geologist home and took over.Around the same time my colleague, the chief field engineer also showed up, so we discussed the situation together with the tool pusher and got a better idea about what had occurred so far in the incident.Essentially, without any warning, the mud system in the well came roaring back up the hole and blew out through the top of the drill stem, creating a plume about 60 feet high.The plume grew rapidly from there to about 125 feet tall (well above the top of the rig), and changed from a mud and water slurry to almost pure gas condensate vapor (liquefied natural gas), an extremely dangerous substance.

Oil Well Blowout

This might have caused an explosion, but we had a great rig crew, so it didn’t.The driller had immediately triggered the dead man’s switch, cutting all motors, and then engaged the blowout preventer, or “BOP.”At first we thought this had worked, and he had stopped the blowout in its tracks.Unfortunately, these actions worked only for a while, and did nothing to permanently stop the blowout.The “BOP” ultimately didn’t work because it only seals off the inside of the pipe; our blowout had so much pressure behind it that when the “BOP” was engaged, the gas was rerouted and ended up coming to the surface via the annulus, or area between the pipe and the wall of the hole, so it could not be stopped by the closing of the “BOP’s” rams.We spent the next 60 hours trying every engineering trick in the book to seal off the blowout and stop the huge flow of natural gas condensate.While we worked we had to keep our eyes on the wind sock to make sure we were upwind all of the time, because condensate can kill you even when it’s not burning.This can happen simply because it’s heavier than air, and can flush all of the oxygen out and asphyxiate you if you’re overtaken by the cloud of vapor.

To make a long story shorter, the gas was flowing out under pressure, about 4,000 psi to be exact, and nothing we had available could hold that kind of pressure down.During a lull in the action, I sat down and looked carefully at the well data to try and figure out what had happened.Eventually I was able to show that we had crossed a fault within the very thick Cretaceous Pierre Shale, and that fault was supercharged with natural gas under pressure.Anyway, we threw everything but the kitchen sink in the hole, and it all came back at us in short order.We tried increasing the mud weight dramatically; then we tried pumping marine cement in under pressure.Nothing worked.Finally we decided to use the old-fashioned oil patch “last resort,” which was to pump the drill-hole full of a bauxite (aluminum ore) slurry that was very heavy, and then we followed that with sticks, pebbles, cement, and anything else we could find.

If it had worked, we would have in the process made it difficult to complete the original drilling plan, and elevated well costs already guaranteed that even if we hit a good pay zone deeper down, the well was not likely to ever make money; but at least the blowout would have been contained.However, even that final effort failed, so we called Boots and Coots, the emergency well control firm, and put them on standby.Calling an emergency well-control firm was the real “last resort,” because the cost of the blowout would have “exploded” higher if they had to deploy their emergency team on the well.But then a few hours later, the well stopped all by itself, literally because it had run completely out of gas.We had nevertheless spent about $100,000 in 1982 dollars on emergency well control measures in just three days.Shortly thereafter the rig of a rival firm hit the same fault about 80 acres away from us, but they weren’t as lucky.Their rig caught fire, everyone got burned (none fatally), and the flames were so hot that part of their rig literally melted into a pool of glowing liquid steel.

I’ve retold this story because it involves an example of a situation in which circumstances were so dangerous that “last resorts” had to be tried.The French have a phrase they use to describe such a situation: we were using a “pis aller,” which means simply that we followed a course of action that was extreme; i.e., it was our absolute “last resort.”How is this relevant to the markets?I believe that sometime in the next few months, or perhaps as much as two years, we may face another great economic crisis that could be as devastating as the one in 2008.There are things that could probably be done to delay this crisis, but it is highly unlikely that we will get away completely unscathed.So we will be forced to apply extreme remedies.To explain my thinking on this, I would ask the reader to bear with me as I recount a brief history of the last crisis, compare that to present circumstances, and then suggest a pis aller, or last resort that could potentially be used to mitigate the huge damage that such a crisis might entail.

A Sign of the Times in 2008

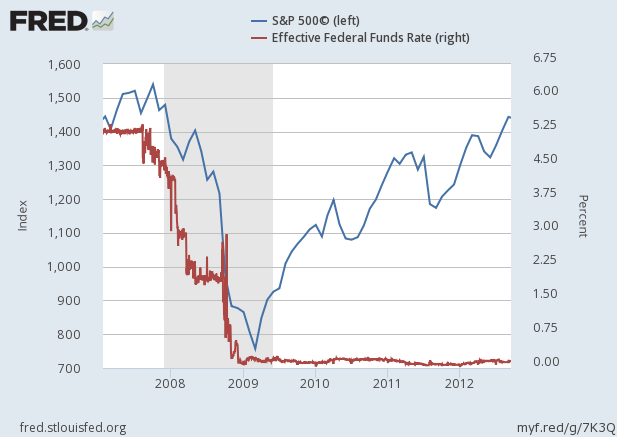

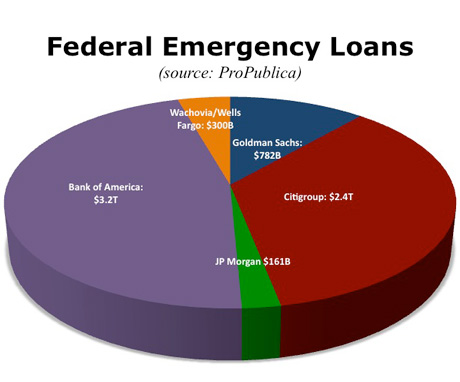

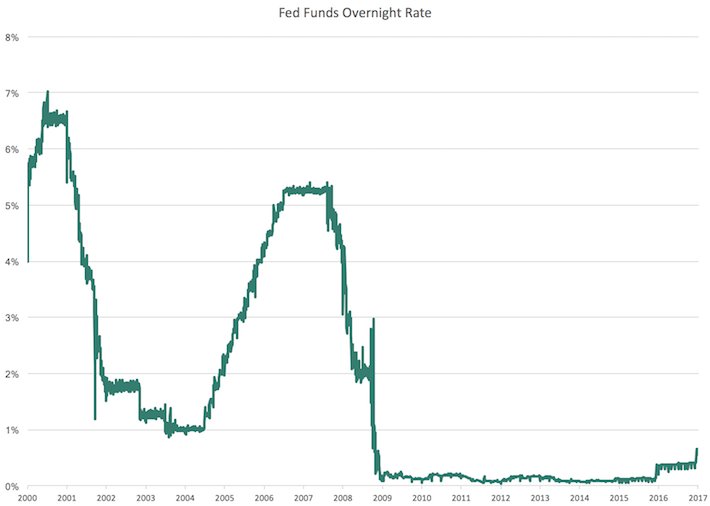

There was such a deep sense of panic and crisis in the halls of government in the fall of 2008 that every conceivable kind of “last resort” was tried out.Each new measure was even bigger and more extreme than the one before it, with fantastic sums of money being thrown at the problem from every part of government.It is in fact difficult to define which of the many extreme measures undertaken would qualify as the “pis aller” of the crisis.My favorite for this honor is the clandestine provision of huge (trillion dollar) loans by the Fed to banks and insurers that were supposedly safe.It was so bad at one point that Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson famously suffered a collapse from the strain of it all.The fear was so enormous that in the end, even blatantly unconstitutional measures were considered perfectly acceptable, by both the Treasury and the Fed.Congress had its doubts but went along anyway.The standard response of the Fed, which is to lower interest rates dramatically in a crisis, was taken to the extreme of the zero bound by December 2008, and this descent happened very rapidly. Yet this demonstrably had no effect on the markets (Chart 1).All manner of liquidity support programs (Chart 2) were also put in place by the Fed and other central banks, acting as lenders of last resort, including direct bailouts of GSE’s (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), and direct bailouts of individual corporations (e.g., AIG). I have said elsewhere how wrong-headed this kind of intervention was.Anyway, direct fiscal intervention was added by Congress and the Bush Administration, most notably via the infamous TARP funding program ($350 billion in the first funding tranche) for banks, but that was completely dwarfed later by the then-secret Federal Reserve bailout funds ($7.7 trillion in loans) given mainly to the largest US financial corporations (Chart 3).Another $9 trillion was loaned out to foreign corporations.

Chart 1: Lack of Market Response to Fed Rate Cuts in 2008

Chart 2: The Fed’s Publicized Special Liquidity Programs in the Crisis

Chart 3: The Fed’s Secret Corporate Loan Program Dwarfed Even the TARP Bailout Program

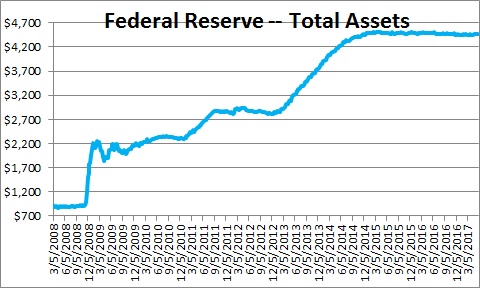

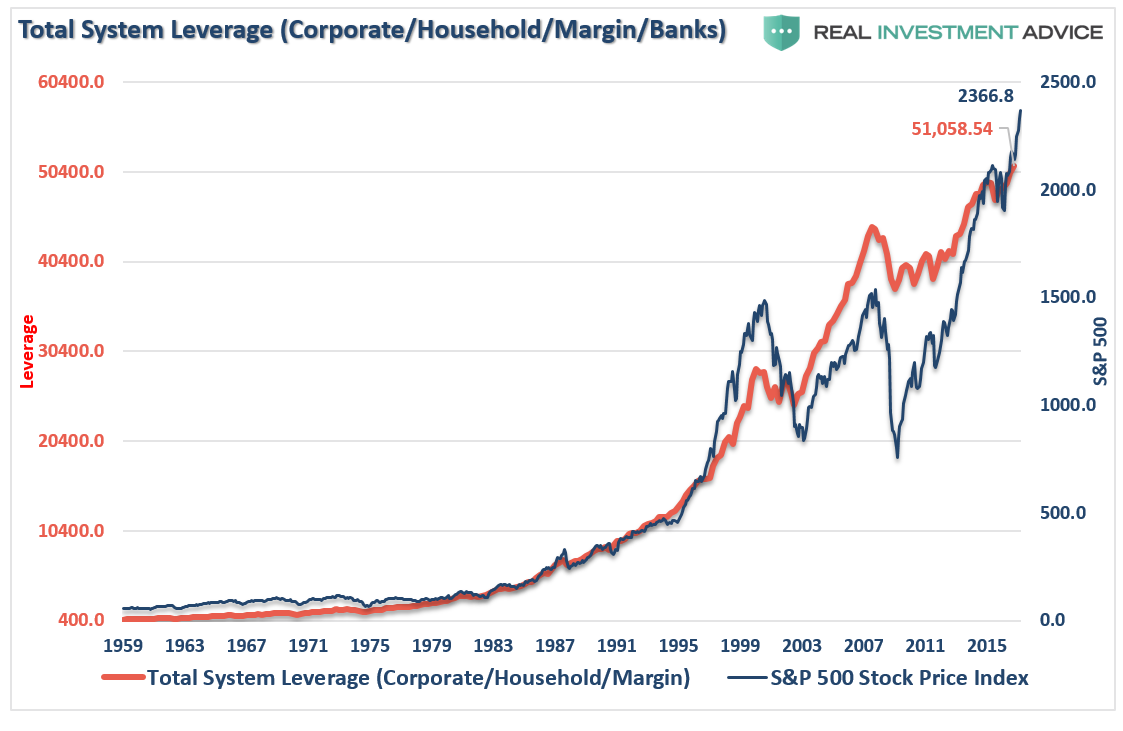

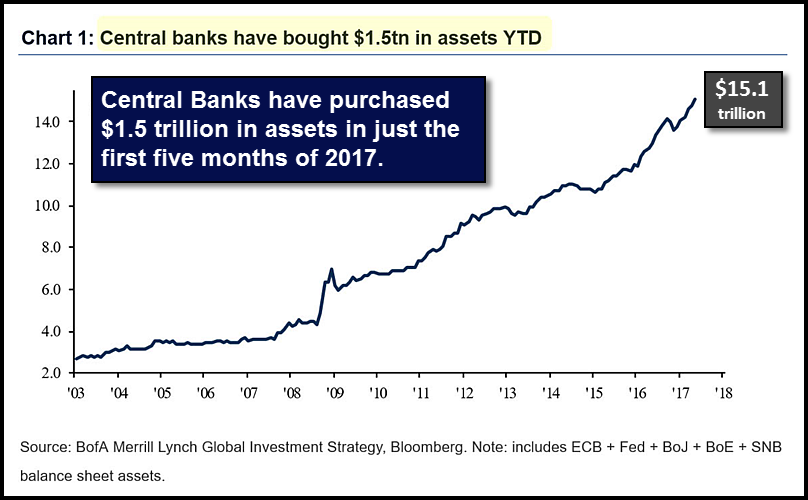

Beginning in November, 2008, Quantitative Easing (QE1) was also utilized by the Fed, which involved directly injecting huge volumes of digital money ($1.4 trillion during QE1 alone; Polyana da Costa & Crissinda Ponder, 2011; http://www.bankrate.com/finance/federal-reserve/financial-crisis-timeline.aspx) into the fixed income markets.Famed economist and fund manager John Hussman (2009; http://hussmanfunds.com/wmc/wmc090406.htm) maintains however, that nothing really worked until TARP, QE1, and TALF were followed by the SEC/FASB decision to partially suspend the mark-to-market rules (FAS-157) for the big banks on April 2, 2009.Certainly that is when markets really took off again, and sentiment simultaneously moved upwards from the extreme lows of early March, 2009.Even today, big banks still have artificially jiggered P/E ratios because of the 2009 partial suspension of fair value accounting rules.What is equally astounding is that the crisis was never really declared over; we still have an immense Federal Reserve balance sheet (Chart 4), very high total debt (Chart 5), deeply suppressed interest rates (Chart 6), tremendous and unneeded excess reserves (over $1.2 trillion) at banks, and global QE continuing as if the crisis had never ended (Chart 7).

Chart 4: The Fed’s Balance Sheet Is Still Massively Bloated

Chart 5: Total US Debt At New High

Source: http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-06-29/yes-ms-yellen/there-will-be-another-financial-crisis

Chart 6: US Fed Funds Rate Still Very Low

Chart 7: Massive QE Purchases of Assets By Central Banks Continue

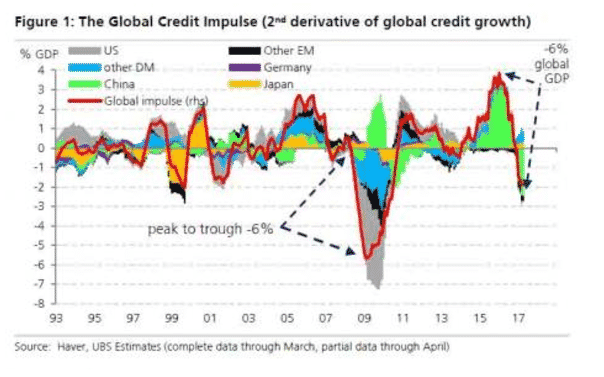

My inclination has been to discount any possibility of a continuing crisis, and to strongly criticize central banks and other government entities for their politically convenient collective belief in a virtually perpetual financial crisis.However, what if we alternatively attempt to return to “normal,” and the result is immediate catastrophic failure?That is what I now fear might happen anyway as several simultaneous new constraints are applied: 1) the Fed raises rates at the wrong time in the cycle, and other central banks (e.g., ECB, BOJ) taper down their QE programs as well; 2) the global credit cycle turns and stays negative; 3) the ballooning cumulative global debt pile that held it all together until now finally stops its expansion, and instead contracts as it reaches its natural (sustainable) limits; and 4) the business cycle hits the limits of resource and capital mis-allocation that generally produce recessions.After all, economic growth has been anemic (Chart 8) for years, productivity growth is nearly flat-lining, consumers and especially corporations are in debt up to their necks (Chart 5 above; also Chart 9), and the global credit cycle is already showing signs of having turned sharply negative (Chart 10).

Chart 8: US GDP Growth Has Been Anemic for Years

Chart 9: US Corporate Debt/Cash Flow At Record Highs

Chart 10: Global Credit Cycle Appears to Have Turned

I believe that the central banks have waited far too long to “normalize” rates.Now it also seems likely that the huge debt load most countries are struggling under gave them few other options, short of letting the system self-correct (not something central planners would even consider).Indeed, seemingly all major central banks and their associated governments have also in effect rejected the basic tenets of capitalism, and so the creative destruction that could have revitalized their economies as a result of normal business failures was mostly negated (as a matter of policy) over the last ten years, on a worldwide basis.“Kicking the can” was, and still is, the standard response of governments nearly everywhere.Hence we observe the ever-growing debt piles, ever-weakening banking systems, ever-more-suspect currencies, and perpetually anemic economic growth that were first seen in aggregate in Japan many years ago (as a result of a debt/deflation cycle), now afflicting many other countries.The result is that in spite of so-called “reforms,” the world is not ready for the next crisis, and in fact is likely to be even less ready than it was in 2008.

Consider this: the banks that were “too big to fail” are much bigger now than they were in 2008.The global debt overhang that led to a global financial crisis has grown by another $74 trillion (!) in the nine years since 2008.The notional (gross) value of the derivatives books held at just the six largest US banks amounts to a whopping $239 trillion, and although the net amount ($3 trillion?) is smaller by far, we still have no way to evaluate the systemic risk exposure, because banks are still allowed to game the system using foreign subsidiaries.In fact, the top six US banks are so complexly structured that they collectively own over 14,400 subsidiaries!The Kansas City Fed has estimated that it would take 70,000 staff just to regulate the top six banks adequately, which they obviously don’t really do.

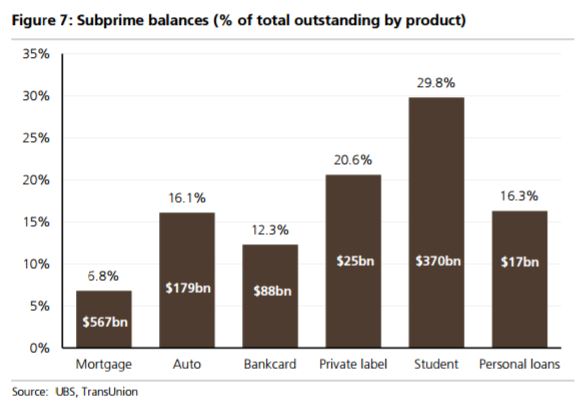

In effect the central banks, by bailing out all comers in 2008, have created the biggest moral hazard problem in world history.The secret loans from the Federal Reserve to big banks were met with a wave of insider trading, but were followed by no prosecutions for the same, as the $7.7 trillion in secret loans were considered “immaterial” and did not even have to be reported.Indeed, in the end virtually no one went to jail for some of the biggest frauds (leading to the crisis) ever perpetrated in human history.Even the ratings agencies, which were at the center of the financial crisis and lost all credibility as a result, were not ever reformed in any substantive way (Sid Verma, 2017; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-02/the-great-escape-how-the-big-three-credit-raters-ducked-reform).This means that some of the same games that led to the 2008 fiasco are already being played for big money again (Chart 11), naturally.So the US already has over $1 trillion outstanding in various types of subprime loans again.

Chart 11: Subprime Debt Starting to Look Like Trouble Again

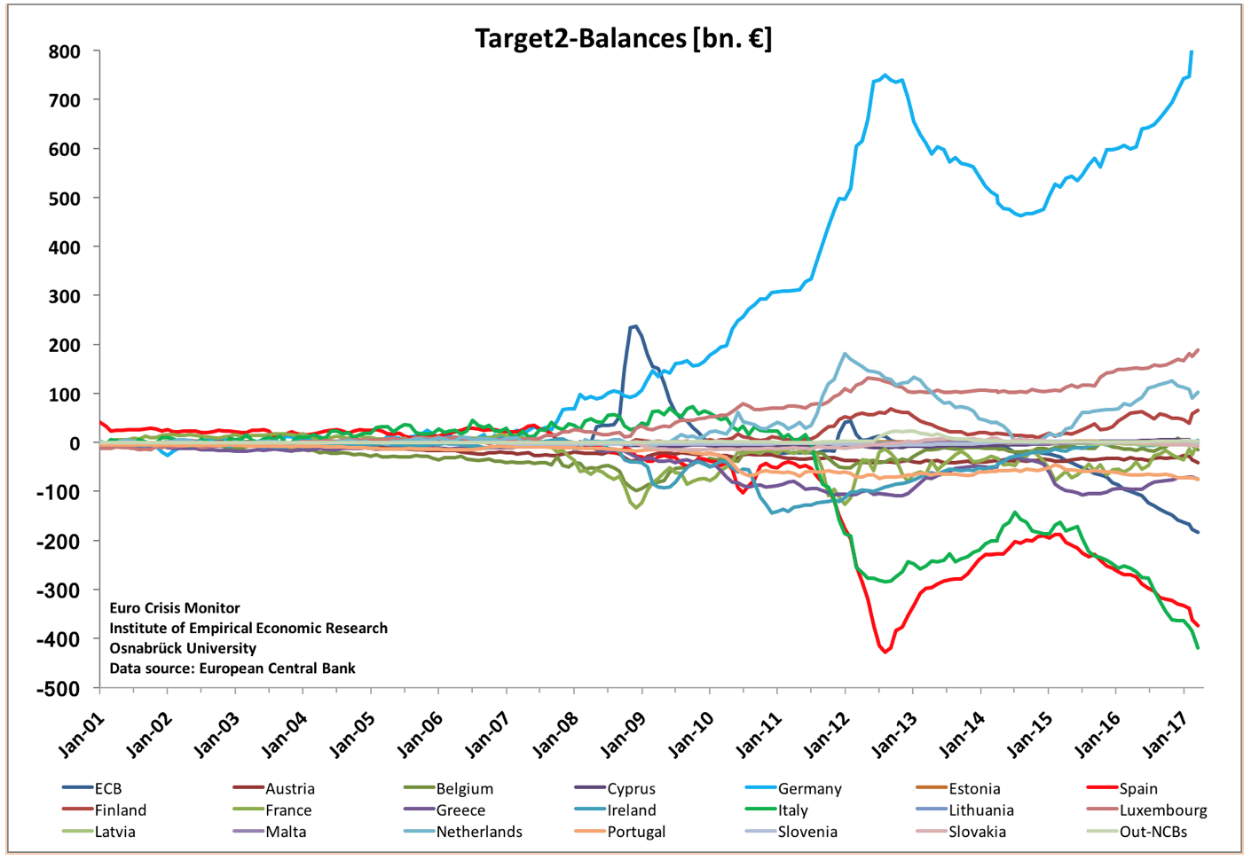

Banks and insurance companies have improved their leverage exposure in some countries (e.g., the USA), but in many other countries (e.g., in the Eurozone) this issue has not been resolved even after nine years.Either way, reduction of leverage alone is no guarantee of safety in the next crisis.For example, most of the expanded bank capitalizations (>80%) now in place are in the form of debt, not the equity that would prove more supportive in a crisis.The huge and opaque derivatives books that helped to cause the 2008 liquidity panic (discussed above) are still in place, and still poorly understood.The EU still has no effective banking union and will not have even a 1% backup system (similar to FDIC) for deposits until 2023 (Mish Shedlock, 2017; https://mishtalk.com/2017/07/31/eu-deposit-insurance-a-bank-crisis-in-italy-and-greece-and-the-coming-ban-on-cash/#more-47125). Not that 1% backing on deposits would prove adequate anyway, either in Europe or in the US.Non-performing loans (“NPLs”) in the EU now total over $1 trillion, and about $276 billion of that “NPL” total is in Italy alone.The “NPL” ratio is an alarming 15.3% in Italy, 19.5% in Portugal, 44.8% in Cyprus, and 45.9% in Greece; all of these contrast sharply with the current 1.3% “NPL” ratio in the US (down from around 8% in the financial crisis).Capital outflows (negative Target 2 balances) from the southern tier of countries to Germany have now exceeded the level seen in the 2011-12 crisis (Chart 12).Banks are so weak in Europe that a financial crisis there is again possible, and indeed, even highly probable; if it happens, it would be likely to involve contagion that would soon make the crisis turn global.

Chart 12: Other Countries Now Owe Germany $800 Billion

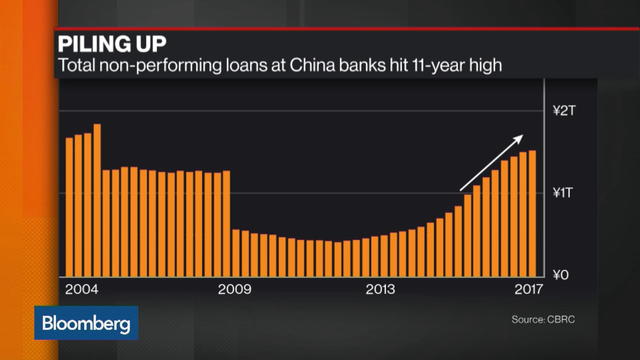

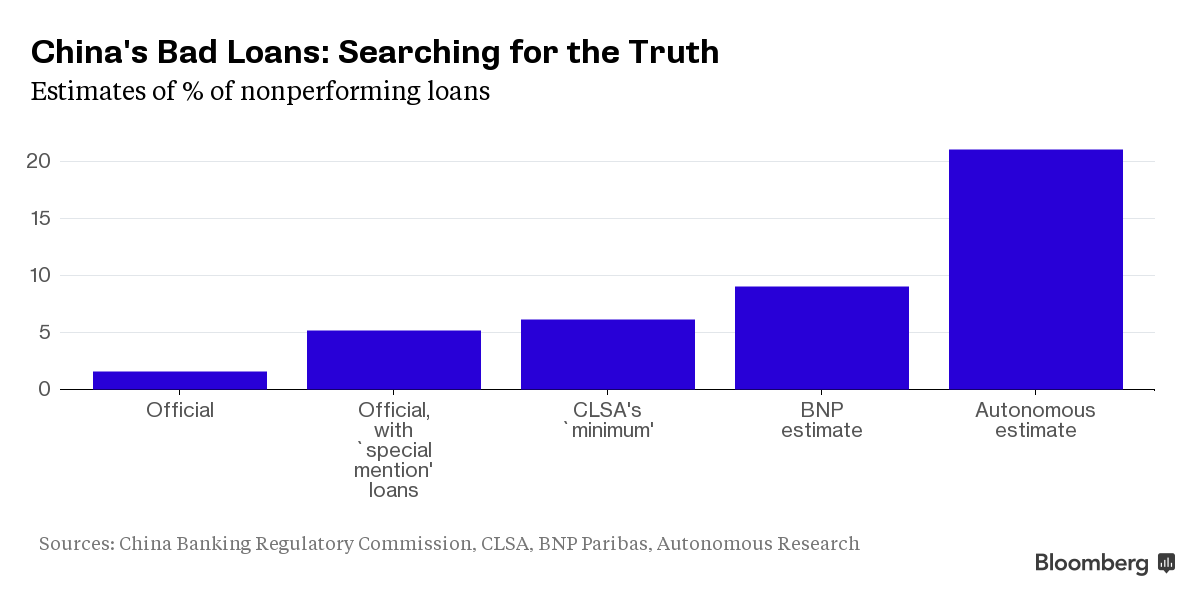

The Chinese have meanwhile built an enormous conventional bank, and unconventional non-bank debt pile (Chart 13) to combat the 2008 financial crisis and sustain GDP growth, with total debt now above 300% of GDP.In fact, Chinese debt now totals about $29 trillion in absolute terms and is still climbing steeply.The Chinese “shadow banking” system (outside regulatory control) has also expanded greatly, as have loans to “SOE’s” that often have trouble paying them back.A large proportion of recent loans in China involve the refinancing of “NPL” debt to avoid reporting losses.The result is a Chinese “NPL” ratio that is now climbing rapidly (Chart 14), reaching at least $218 billion in early 2017.Some suggest that the government’s numbers are highly suspect, and that the real number is five or even ten times as high – in other words, trillions of dollars (Chart 15).If this is so, then China’s recent crackdown on debt issuance makes plenty of sense (Kevin Hamlin, 2017; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-01/can-xi-jinping-defuse-china-s-debt-bomb).It would also be true that until this situation is eventually resolved, future problems with the Chinese debt overhang could be a major catalyst in setting off another global financial crisis.Although China’s savings rate is high and supports the current debt level to some degree, without reforms it is likely that China will soon reach a natural limit on the size of the debt overhang.Any financial crisis then beginning in China would also likely spread rapidly through contagion to the rest of Asia and to Europe.

Chart 13:Chinese Debt Now Above 300% Relative to GDP

Chart 14:Chinese “NPLs” Increasing Rapidly

Chart 15: Actual Level of Chinese “NPLs” Is Disputed

John Maxfield of the Motley Fool blog (2015; https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2015/02/28/25-major-factors-that-caused-or-contributed-to-the.aspx) wrote recently that there were as many as 25 contributing factors to the financial crisis in 2008.We have already discussed a number of these factors in the present article.What is disturbing though, is the fact that so many of them are still with us, or have returned to haunt us again.For example, we still have bond ratings that are sourced from highly compromised ratings agencies that, while chastened a bit, have still not been reformed.Big banks are still securitizing subprime loans, although not with quite the level of abandon that was seen in the years before 2008.Credit default swaps and other derivatives are supposedly organized in open exchanges now, where their opacity (and counter-party risk) is somewhat or greatly reduced; however, big US banks have sent an undetermined amount of their derivatives business to their foreign subsidiaries to avoid scrutiny.

Almost no one was prosecuted for fraud in the biggest financial scandal in human history, but many investment banks and bankers were rewarded with secret bailouts and opportunities for insider trading instead.Their impunity regardless of behavior has created world class moral hazard, and we are unlikely to escape their clutches unscathed.Banks around the world still have enormous off-balance-sheet risks that have not been properly discounted by either regulators or the markets.In a crisis, that will again change.Meanwhile, the Greenspan put became the Bernanke put, and then the Yellen put.But the put assumed to back the markets has no buying power, because rates are still near zero and central bank balance sheets are already extremely bloated.What then is left in central bankers’ quivers for the next big disaster, if it comes now rather than ten years from now?Japan provides the clue, once again: central banks will completely destroy the markets by taking them over.Equities and junk bonds will be bought in huge quantities, in what will be the “pis aller” move of the century. The only alternatives will be: 1) ineffectual bond purchases under a new QE phase that can’t reach big enough volumes to work; 2) helicopter money drops, a form of “pis aller” that will only work if done once, massively, and never repeated; or 3) letting the chips fall where they may.

I have no idea which of these problems will explode into the next financial crisis.Maybe through some combination of circumstances, none of them will directly cause a crisis.But they could indirectly make one that starts somewhere else (e.g., emerging markets) get much worse, in a hurry.The problem is that conditions are conducive to a sudden spike in potential danger; we have in effect placed explosives in the road to economic growth and are now pouring gasoline all over everything.I believe a small spark (i.e., economic shock) will be all it takes when the time comes.Our situation then, is arguably very similar to the situation prevailing in 2007.We are approaching the abyss, but except for widely ignored warning signs, we seem once again collectively sure that years of tepid global economic activity combined with extreme market highs are signaling low overall risk, when in fact they are signaling the exact opposite.

This time around we may not get the luxury of a long lead-in time to the crisis.In 2006 the yield curve inverted, sending the clearest of recession signals way in advance, but almost everyone ignored it.Those who did not ignore it, or other damning evidence (e.g., Dean Baker, John Hussman, Paul Kasriel, Steve Keen, John Mauldin, Ann Pettifor, Raghuram Rajan, David Rosenberg, Nouriel Roubini, Peter Schiff, and Gary Shilling) were first ridiculed or ignored, but then eventually lionized as great seers (cf. Cameron Cooper, 2015; https://www.intheblack.com/articles/2015/07/07/6-economists-who-predicted-the-global-financial-crisis-and-why-we-should-listen-to-them-from-now-on).Many other indicators besides the yield curve inversion accumulated before the actual crisis hit.I personally followed the evidence presented by many of these analysts in real time, which led me to the same conclusions, and so I was ready for the crisis when it came.This saved my clients millions in paper losses as a result.However, there may not be any simple diagnostic like a yield curve inversion this time; or if there is, it will come almost too late to matter.

There is a substantial risk of an economic shock in the coming 24 months or so.We have unpredictable European elections coming; continuing political dysfunction in the US; a US debt ceiling crisis on the way; troubles with North Korea, Iran, China, and Russia; wars against ISIS and the Taliban; and economic disturbances in the UK, China, the Middle East, and Japan.There is also a real risk of a sudden drop in the markets once the full extent of the coming economic trouble is realized. A waterfall market meltdown like 2011, 2008, 1987, or even 1929, is entirely possible, given extreme valuations, and the approaching end of the business and credit cycles. As I have written elsewhere, this market is priced to perfection and will be intolerant of even the slightest change in the major assumptions underlying the rally.Market breadth is poor (Brad Lamensdorf, 2017) and market internals in general are fiercely negative (John Hussman, 2017).

Those in a more defensive frame of mind because of the expected troubles discussed above should hold some intermediate to long Treasuries: the Wasatch-Hoisington US Treasury Fund (WHOSX), the I-Shares 20+ Yr. Treasury Bond ETF (TLT), the Vanguard Intermediate Term Bond Fund (BIV), the PIMCO Total Return Active ETF (BOND), and the DoubleLine SPDR Total Return Tactical Bond Fund (TOTL); also some liquid alternatives like the Otter Creek Prof. Mngd. Long/Short Portfolio (OTCRX), the AQR Long/Short Equity Fund (QLENX), and the AQR Managed Futures Fund (AQMNX).

Disclaimer:This article is intended to provide information to interested parties. As I have no knowledge of individual investor circumstances, goals, and/or portfolio concentration or ...

more