Negative Rates And Central Banks

With forecasts of a slower global economy, central banks around the world are once again contemplating that they might need a much easier monetary policy.

The problem is that monetary policy is already in an “easy” mode and has been this way for about a decade.

This presents serious constraints on just how much more stimulus monetary policy can provide. Once again, other policies may be needed to support private spending, specifically expansionary government fiscal measures.

As matters currently stand, the conventional monetary policy instrument – short-term interest rates – is already close to zero in Europe. Even the United States, which has the fed funds rate at around 1.75%, currently does not have much flexibility to lower rates before it too falls to zero.

In past American recessions, the federal funds rate typically fell 300 to 500 basis points. For example, in the case over the 2007-08 financial meltdown, the federal funds rate fell from over 5% to almost zero. This kind of an interest rate stimulus is clearly not available should the American economy stumble into another recession.

The financial community is understandably reluctant to endorse the goal of pushing past zero and pursuing negative interest rates to stimulate lending and boost a weak economy. This is understandable since negative interest rates are potentially harmful to the banking sector and to consumer confidence.

Until recently it was assumed that central banks in setting overnight lending rates, did not have the ability to push the nominal interest rate below the limit of 0%, into negative territory.

In fact, negative interest rates albeit unconventional seemed to work.

For example, the ECB introduced a negative rate policy (a charge for deposits) on overnight lending in 2014. And Japan has had considerable experience with negative rates because during most of the 1990s, the interest rate set by Japan’s central bank, hovered around zero.

The BOJ formally moved to negative interest rates in 2016, by charging depositing banks a fee to store their overnight funds.

In any case, governments should not be spooked against aggressively using fiscal policy if an easier monetary policy is a problem.

After all, with interest rates so close to zero, this is the perfect time to issue long-term public debt at essentially zero real interest rates.

Indeed, for both the US and Canada the timing couldn’t be better for funding needed infrastructure projects which would increase both productivity and support economic growth and jobs.

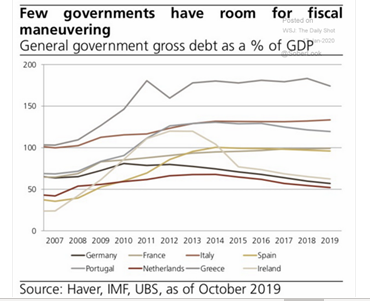

Unfortunately, not all advanced countries are in the same position in terms of available fiscal space. Some countries have a lot of space (i.e. Canada, Germany, the US?), and others feel they have less room due to too high levels of government indebtedness and/or currency worries.

The following chart illustrates how in Europe, Germany clearly has the largest room to maneuver to provide a fiscal stimulus, if it so chooses.

(Click on image to enlarge)