Fish Stocks And Our Balance Of Payments

Our balance of payments is overly burdened by our consumption of seafood: We import approximately 90% of the seafood that we eat. Given our natural resources, we should be net exporters of seafood.

The total value of edible and non-edible fishery imports in the United States was $35.8 billion in 2016. The total value of edible and non-edible exports was $21.3 billion.

The imbalance does not imply only a shipment of dollars abroad. It also implies a number of jobs exported, a number of jobs that could be created in this country, were we not to import that much more seafood than we export.

Why this imbalance?

Before answering this question, allow me to introduce myself. I have studied fisheries issues for about fifty years; I am the author (with Louis J. Ronsivalli) of Quality Assurance of Seafood (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1988); through this work, we introduced fresh fish into the nation’s supermarkets; I have published numerous papers and articles in fisheries development.

The reason for the imbalance in our accounts with other nations is not due to lack of fish in our waters. Not to put too fine a point on it, the imbalance is due to rules and regulations imposed by our National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) that prevent our fishermen from catching fish.

These rules and regulations are imposed to prevent overfishing, a potential exploitation of the fisheries to the point of endangering the existence of stocks of fish in the future. This is an assumption that is born neither by science nor by the facts.

Most of the times, fishermen bitterly proclaim that there are fish in the oceans, but they are prevented from catching them by arbitrary rules and regulations promulgated by NMFS.

The mathematical formula on the basis of which NMFS makes its determinations contains all sorts of data, but no science. In addition to historical data, which are not valuable because they report past catches that are constrained by the given administrative rules and regulations, historical data are also ill recording the reality of fish stocks because of many unknowns in the number and types of discards. Data are based on crude estimates, and much ideology, but no science, because no science of fisheries stock assessments is known to NMFS.

Yet, contrary to ongoing assumptions and practices, there is a science of stock assessments. This science represents the observed behavior of all biological species on land as well as at sea—even trees, it has been discovered, obey the same laws of nature. This science is represented by the predator/prey model, which has been explored ever since Lotka and Volterra demonstrated in the early 1900s that the periodic disappearance of anchovies in the Adriatic Sea was due—not to fishermen’s overfishing—but to the abundance of their natural predators.

A study of New England Fisheries that I commissioned in the early 70s, while I was Director of Planning and Economic Development of Action Inc. in Gloucester, MA, from Joe Wohl, a Draper Laboratory scientist who had contributed to sending a man to the moon, and safely back, shows that the mathematics of this science, nonlinear math as used in chaos theory, is extremely complex. And this complexity is one of the reasons why this science is not yet used by the National Marine Fisheries Service in its determination of stock assessments.

Instead of using this science. NMFS also uses surveys to make its determinations. But this is an upside-down use of the science of surveys. Surveys are efficient because we know the "universe"; we then build a "sample" that represents the universe as faithfully as possible. And then we draw conclusions from the results of surveys.

In fisheries management, instead, we use samples to discover the universe (!), the universe of fish living in the immense and changeable expanses of the ocean.

The dynamics of the biology of fish growth is evident to the mind to be seen: The larvae of bottom fish rise to the surface of the ocean for food (plankton) and light. In the process, they are met by the pelagics, fish that live in the middle of the water column, and are devoured. Those bottom fish that survive, once they become codlings need to go down to their habitat to live among "friends and relatives" at the bottom of the ocean. And, again, codlings are met by the pelagics on the way down and devoured.

Biologists within NMFS have indeed found codlings in the stomach of pelagics.

It is this dynamics that dictates the existence of the predator/prey relationship. In this phase of the cycle, pelagics are predators and bottom fish are prey.

Once stocks of pelagics grow disproportionately, they collapse for at least two reasons: They become so dense that they are deprived of oxygen and beach themselves in huge quantities; their stocks also collapse for eventual lack of their primary food resource, bottom fish.

Once pelagics collapse, room is created for the growth of bottom fish. In this phase of the cycle, bottom fish become the predators and pelagics the prey.

There are two more phases to the cycle: One, in which both predators and preys grow together; the other when they decline together. This is also the cycle of night and day, light and darkness. At sunrise and sunset, light and darkness are fused together.

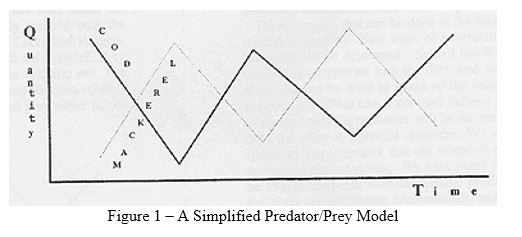

Thus, it is apparent that the geometry of the science of the predator/prey model, as it can be seen from the following diagram, is very intuitive. When mackerel (one of pelagic species) stocks go up, cod stocks go down. Predators at one moment become preys at another. The graph shown here is a two-phase diagram. A more complete diagram shows that there are two more phases to the natural cycle: To repeat, there is a phase in which both predators and preys grow together and a phase in which both predators and preys decrease together.

Clearly, it will take intensive study by NMFS to ascertain the current status of these biological cycles. And the cycle of bottom fish to pelagics is only one cycle that rules in the oceans: Another cycle is between birds and dogfish, for instance, as predators of pelagics and codlings that come to the surface of the oceans.

Clearly, there are also other forces that rule the biology of fish stocks: Ocean acidification and climate change are among them, and fisheries managers have to work with many other experts on important issues such as these.

Given these complexities, while waiting for detailed scientific studies along these lines, the administration of the science of fisheries stocks assessments can be reduced to this simple formula: NMFS should determine which ones are the abundant stocks of the moment, should inform fishermen of these findings, and then let the family fishermen freely harvest the abundant stocks. With the implementation of this simple, but far from simplistic, rule we might be able to shake the shackles that today burden the family fisherman.

As pointed out in the companion petition that is circulating on the Internet, which without prodding from me has been signed by more than 550 people all over the world, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA), the Congressional Act that controls the fisheries, should be amended to allow family fishermen to freely harvest abundant species, while strict regulations should be prescribed—and enforced—for large corporate fishing concerns as well as for foreign fleets. Congress in its wisdom has already given NMFS the power, via import controls, to pursue both tasks for the avoidance of overfishing.

To penalize family fishermen for overfishing that is not done by them, but is done by natural predators of fish as well as by large corporate concerns and by foreign fleets, while responding to no scientific findings or biological needs, ends up destroying local employment and income of local fishing communities; and structural investments pursued over hundreds of years are, without any reason, going to waste.

We are living a political reality in which US Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, the national Administrator responsible for NMFS, as well as U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke are fully aware of the damage done by rules and regulations that shackle our fishermen.

If the fisheries industry should find the intellectual stamina to make an attempt to amend the MSA, the effort is not going to be a struggle against windmills. There is a good chance of success. The dictates of science might prevail over the dictates of ideology that during the last forty years have nearly destroyed our fisheries and the way of life of too many fishing communities.

With friends high and low, it is possible for the industry to reverse the flow of current trends: jobs will be created within our national borders; the flow of our money going abroad will be reduced; and, given exports overcoming imports, the flow of foreign money coming into our country will be increased. Local communities will be richer.

Disclosure: Carmine Gorga is president of The Somist Institute and a former Fulbright Scholar.