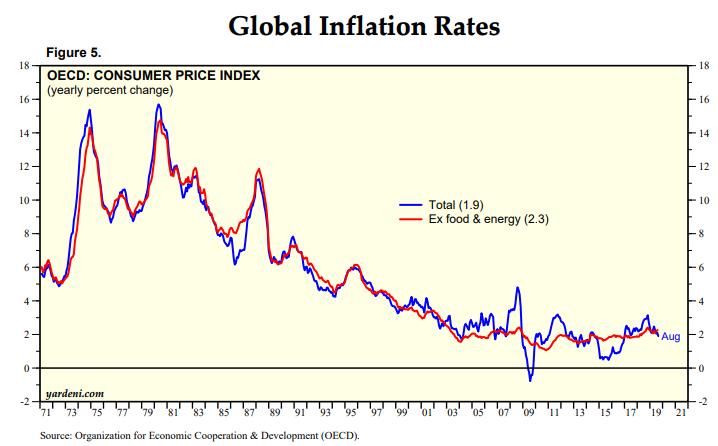

Disinflation Persists

“Weak demand and persistent economic slack have contributed to recent disinflation among advanced and several emerging market economies. But subdued import prices have also played a key role in bringing inflation down. This partly reflects the decline in oil and other commodity prices, but the study shows that the effect of weaker import prices on domestic inflation is also associated with industrial slack in key large economies” (Samya Beidas-Strom et. al., Combating Persistent Disinflation: A Challenge for Many Central Banks, IMF, Sep. 27, 2016)

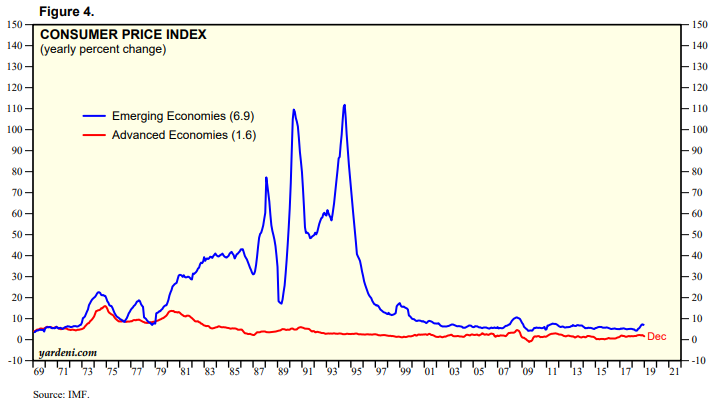

Make no mistake, disinflation or generally weak inflation may become the scourge of the 21st-century economies. Weak or low inflation is worrying central banks and policymakers, and investors should also be concerned about the disinflation trends.

The term disinflation is commonly used by economists to describe a phase of slowing price inflation. A disinflation phase is often thought as a temporary or rather short run.

Disinflation, which is a slowing in the rate of increase of prices sounds a bit better than pure deflation, which is an and out reduction in general prices. But when the rate of inflation is persistently weak, it is also a warning sign that something is very wrong in the macroeconomic environment. This warning sign takes of even greater significance when, as is currently the case, virtually all advanced economies appear to be experiencing very slow inflation combined with relatively strong job market rates.

Disinflation may be the result of many different circumstances. Sometimes it may be due to a central bank tightening its monetary policy, though as well, international events can also spark a deceleration in prices increases.

However, the low and declining rate of inflation which emerged in the aftermath of the Great Recession seems to have become broad-based, as it has affected many industries and different commodity groups.

A short-term phase of declining inflation is not too concerning since its origins can often be traced to a temporary supply shock, such as declining energy prices or unusual productivity gains.

But the worry is that a persistent decline in inflation could turn into out and out price deflation, where the incentives to postpone purchases and investments becomes so entrenched that the overall economy contracts, which in turn reinforces further declines in wages and prices.

Inflation expectations also play a dynamic role in the future of price movements.

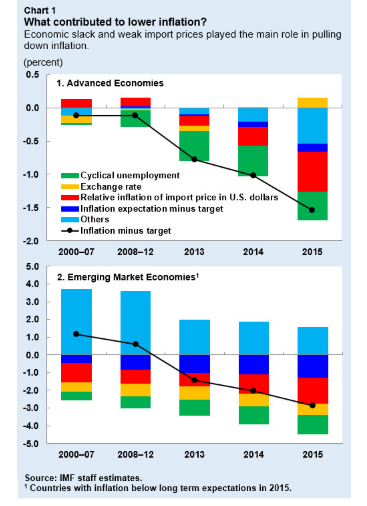

In a recent report, the IMF tried to disentangle the various factors explaining the recent long phase of weak inflation.

In some respects, the findings were understandable. Traded goods had a lot to do with the Post Great Depression weakness in inflation in the advanced economies.

Excess capacity and high unemployment in the advanced economies which followed in the aftermath of the Recession resulted in downward pressure on the prices of tradeable goods and generally reduced import prices. Weak demand and persistent economic slack also contributed to the recent disinflation among advanced and several emerging market economies (Chart 1).

The slack in the advanced economies also spread to the emerging market economies, including China, and also lowered their rate of inflation.

Lower import prices have also played an important role in reducing the general rate of inflation. In particular, the IMF study focuses on the role of the decline in oil and other commodity prices.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)