The Currency Composition Of Foreign Exchange Reserves

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Hiro Ito (Portland State University) and Robert N. McCauley (formerly Bank for International Settlements). The views presented represent those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are or were affilliated with.

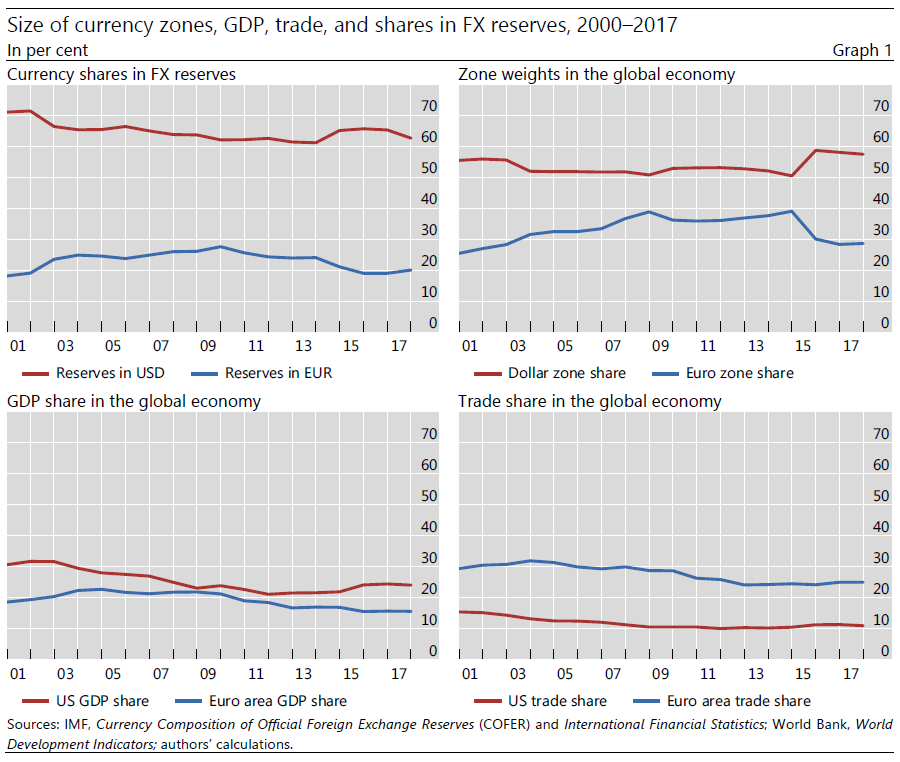

Since 1945, the US dollar has dominated the international monetary and financial system. The dollar plays a particularly out0sized role in official foreign exchange (FX) reserves. Scholars find it puzzling that its share has persisted at about two thirds of the total. After all, the US share of both world GDP and global trade has declined post-war. However, when researchers seek to understand the dollar’s predominance in FX reserves, they quickly encounter severe data limitations that greatly impede empirical analysis.

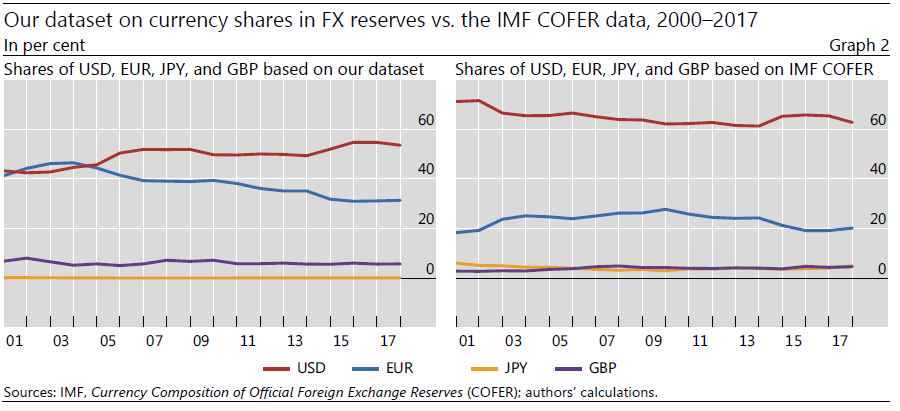

We attempt to remove this impediment in a new working paper. To do so, we compile a data set from annual reports, financial statements and other relevant sources for 58 central banks across the world (in 1999–2017. This data set makes a big contribution. The IMF’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) data generally disclose only aggregates for the entire world, advanced economies and emerging market economies, not data on individual economies.

Our dataset includes 13 advanced economies; 45 “emerging and developing economies”, as defined by the IMF. By region we have 10 Asian-Pacific; 12 African and Middle Eastern; 6 Western European; 17 Eastern European and Central Asian; and 12 Western Hemisphere (We exclude issuers of the key currencies: the United States, the euro area, and Japan).

Our aggregate USD and EUR shares demonstrate a waning European selection bias in disclosure of currency weights (Graph 2). While the IMF COFER shows the USD share has been on a slightly declining trend in the 60-70% range, it starts in our dataset from low levels (ie, 40-45%), and rises in the late 2000s and the mid-2010s. The contrast between our data and the COFER data arise mainly because our dataset, especially in the early years, over-represents European countries that tend to disclose their reserve currency composition. Our lower USD share also arises from our exclusion of Japan and the euro area, whose reserves well exceed US reserves, and which hold high shares (90%?) of USD in their FX reserves.

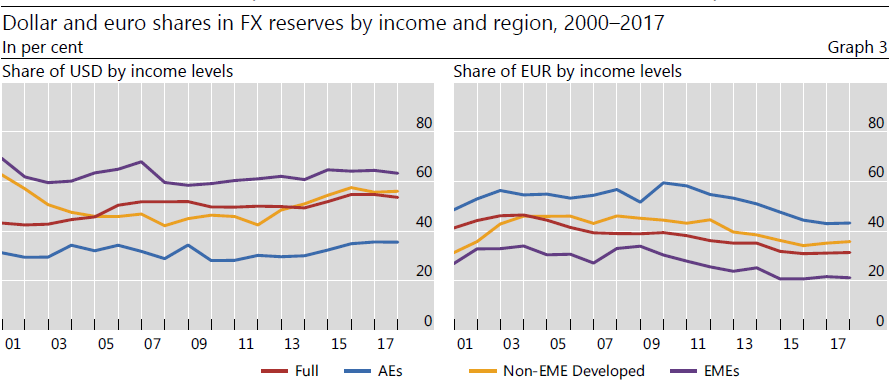

Across income groups, EMEs have held persistently high USD shares in their reserves (Graph 3, top left panel). Non-EME developing countries do not have as high USD shares as EMEs do. AEs hold lower USD shares on average, which reflects that many are (non-euro area) European countries in Northern and Western Europe.

Using this data set, we find that the greater the co-movement of the domestic currency with the dollar (euro), the higher its dollar (euro) share of FX reserves. This finding holds in both the cross section and the panel. This makes sense. If a currency varies less against the dollar than against other key currencies, then an FX reserve portfolio with a large dollar share poses less risk when returns are measured in domestic currency. We also find in smaller samples that the higher the dollar-denominated (euro-denominated) share of exports, the higher the dollar (euro) share in FX reserves. The effect of currency anchoring appears to be on a par with that of the unit of account in trade as determinants of reserve composition.

Disclosure: None.