Buybacks: Why Pipeline Companies Should Invest In Themselves

Weakness in the pipeline sector over the past couple of years has caused soul-searching and changes to corporate structure. Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs), which syphon off a portion of an MLP’s Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) to the General Partner (GP) running it, have largely gone. Many of the biggest MLPs have abandoned the structure entirely, leaving its narrow set of income-seeking investors to become corporations open to global institutions.

The debate among investors, management and Wall Street about how to unlock value received some useful ideas recently from Wells Fargo (WFC). In a presentation titled The Midstream Conundrum…And Ideas For How To Fix It, they make a persuasive case that stock buybacks offer a more attractive use of investment capital than new projects.

This would be a significant shift for MLPs. As recently as five years ago, they paid out 90% or more of their DCF to unit-holders and GP (if they had one). The Shale Revolution was only beginning to demand substantial new infrastructure, so they had little else to do with their cash. New projects were funded by borrowing and by issuing equity through secondary offerings.

Shale plays were in regions, such as the Bakken in North Dakota and the Marcellus in Pennsylvania/Ohio, inadequately serviced by pipelines. This broke the model, because the amounts of investment capital required grew substantially. The capital markets loop of paying generous distributions while simultaneously retrieving much of the cash through new debt and equity was no longer sustainable. Dozens of distribution cuts and lower leverage followed, leading to projects being internally financed. This is the new gold standard for the sector – reliance on external capital to fund growth is out.

Wells Fargo takes this logic a step further, asking why excess cash always needs to be reinvested back in the business rather than returned to investors via buybacks. In spite of professed financial discipline, midstream management teams invariably find new things to build, all expected to be accretive (i.e. return more than their cost of capital). Pipeline companies are not alone – the entire energy sector has been dragged by investors to prioritize cash returns over growth. But MLPs rarely buy back stock. Free of a corporate tax liability, MLP distributions aren’t subject to the double taxation of corporate dividends, so raising payouts is a simple way to return cash.

The Midstream Story over the past several years has largely been about financing growth projects. Investor payouts were sacrificed, but rarely did a company admit that its internal cost of capital was too high to justify a new initiative. Wells Fargo is challenging management teams to regard buying back their own stock as a more attractive use of capital than building or acquiring new assets. This is capital management 101 for most industries, but unfamiliar terrain for pipeline stocks. Growth is embedded in the culture. The original justification for the GP/MLP structure with IDRs was to incent management to grow the business. CEOs in other industries find the motivation without such complexity.

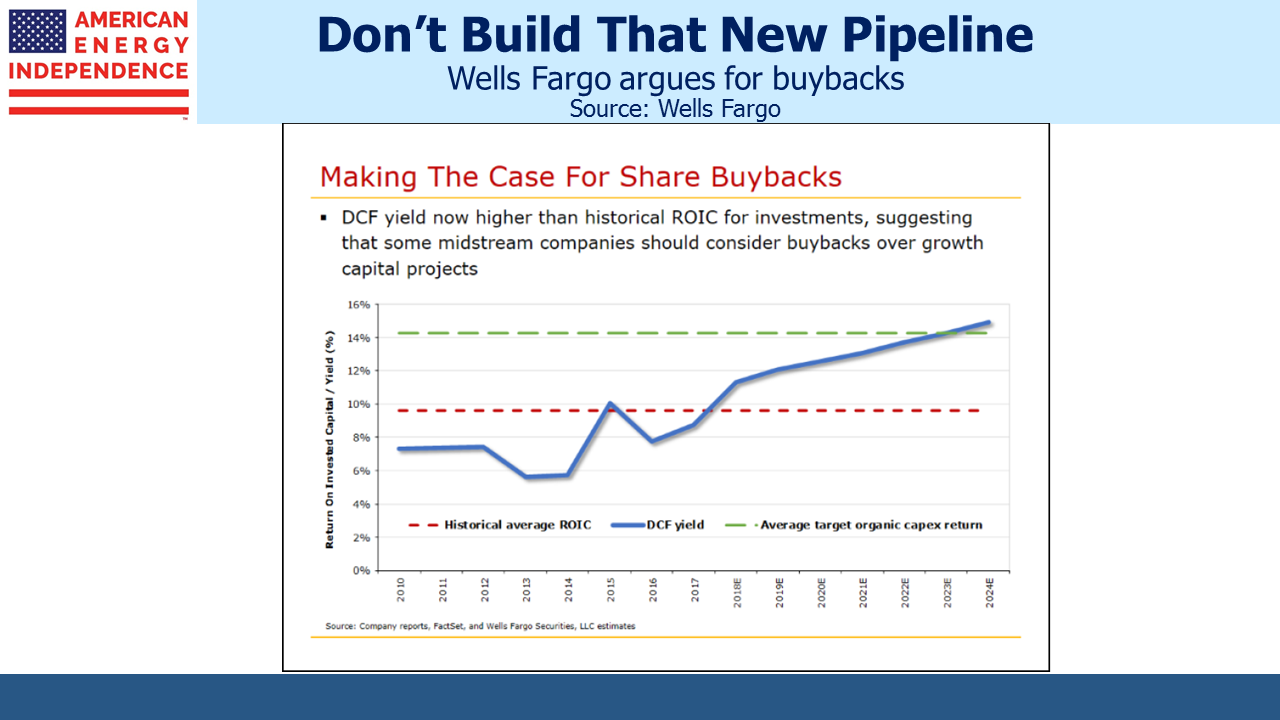

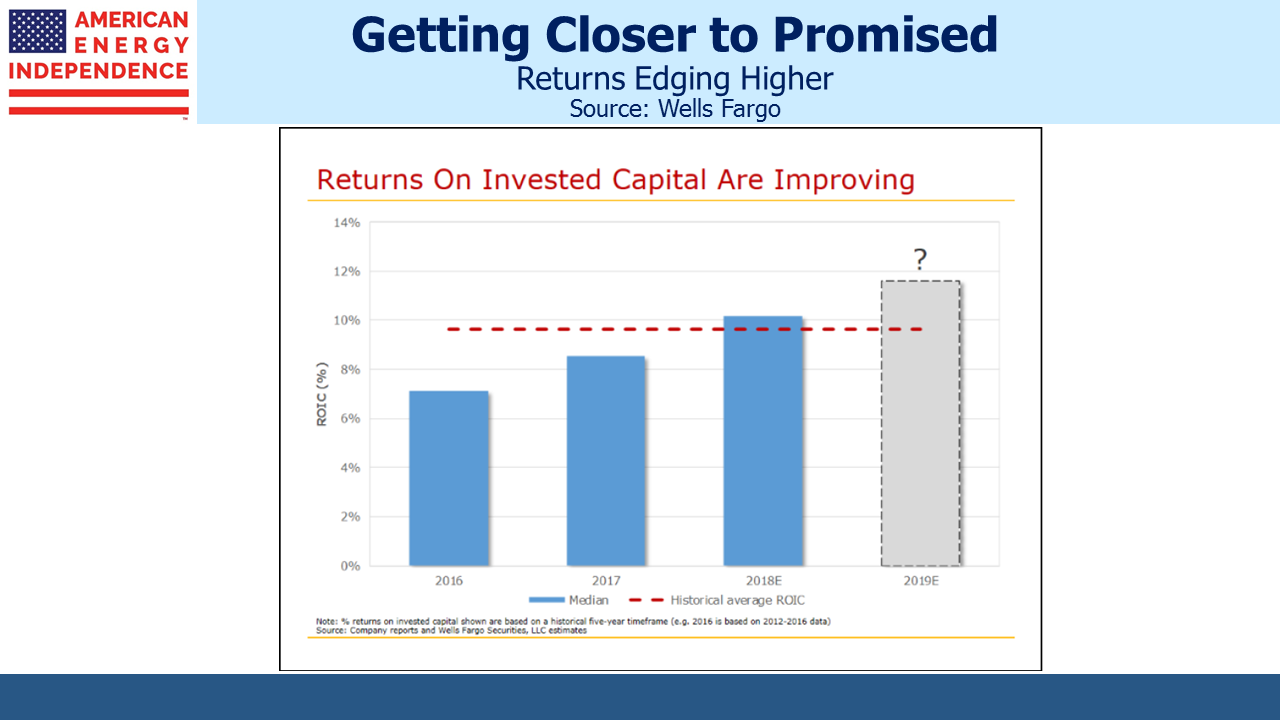

In October, virtually every 3Q18 earnings call included an optimistic outlook from management, usually coupled with disbelief at the continued undervaluation of their stock. Attractive valuations mean a high internal cost of capital. Valued by DCF, or Free Cash Flow (FCF) before growth capex, midstream yields are in some cases higher than many companies’ stated Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) targets. Moreover, historic ROIC for the industry has often turned out lower than promised, although it has been improving.

Energy Transfer’s (ET) 16% DCF yield almost certainly offers a higher return than all but their best projects, and suggests they should be repurchasing stock. SemGroup’s (SEMG) DCF is 20%, twice the industry’s historic ROIC.

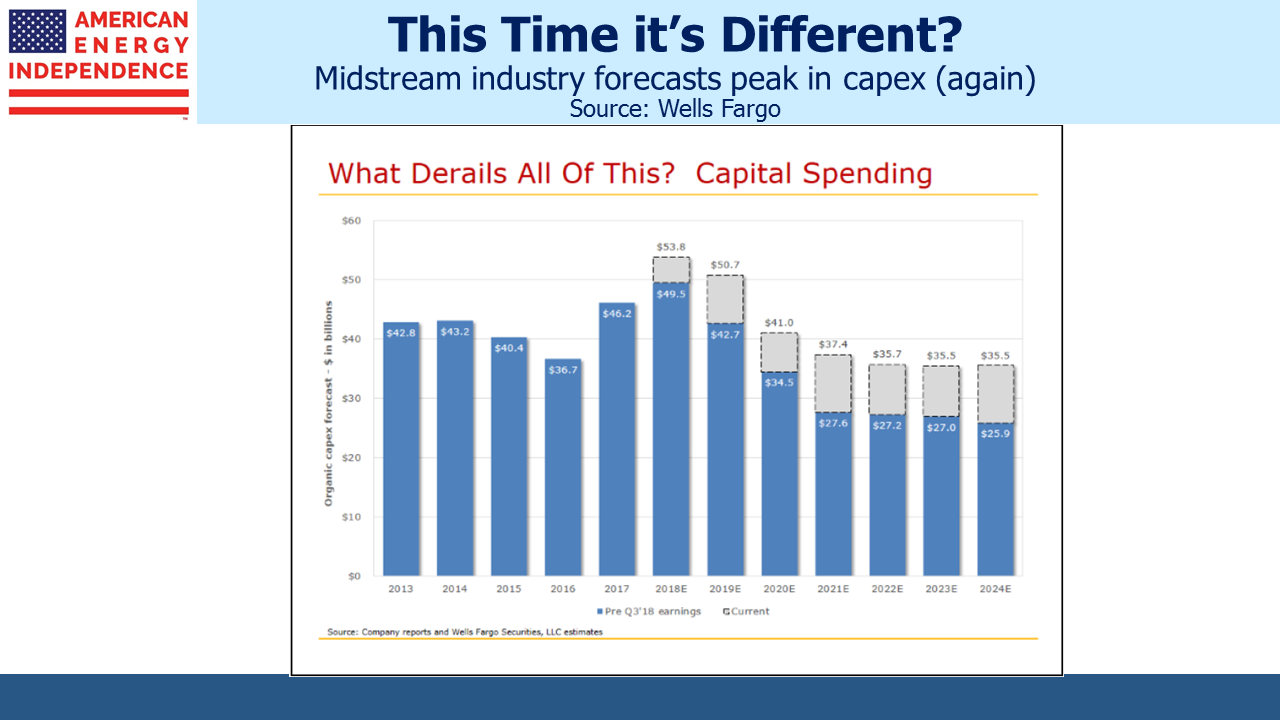

Growth caused the past four years’ upheaval, and today’s low valuations are the result. Capital discipline has been less present than CEOs often claim, which is why they’ve apparently responded coolly to Wells Fargo’s buyback recommendation.

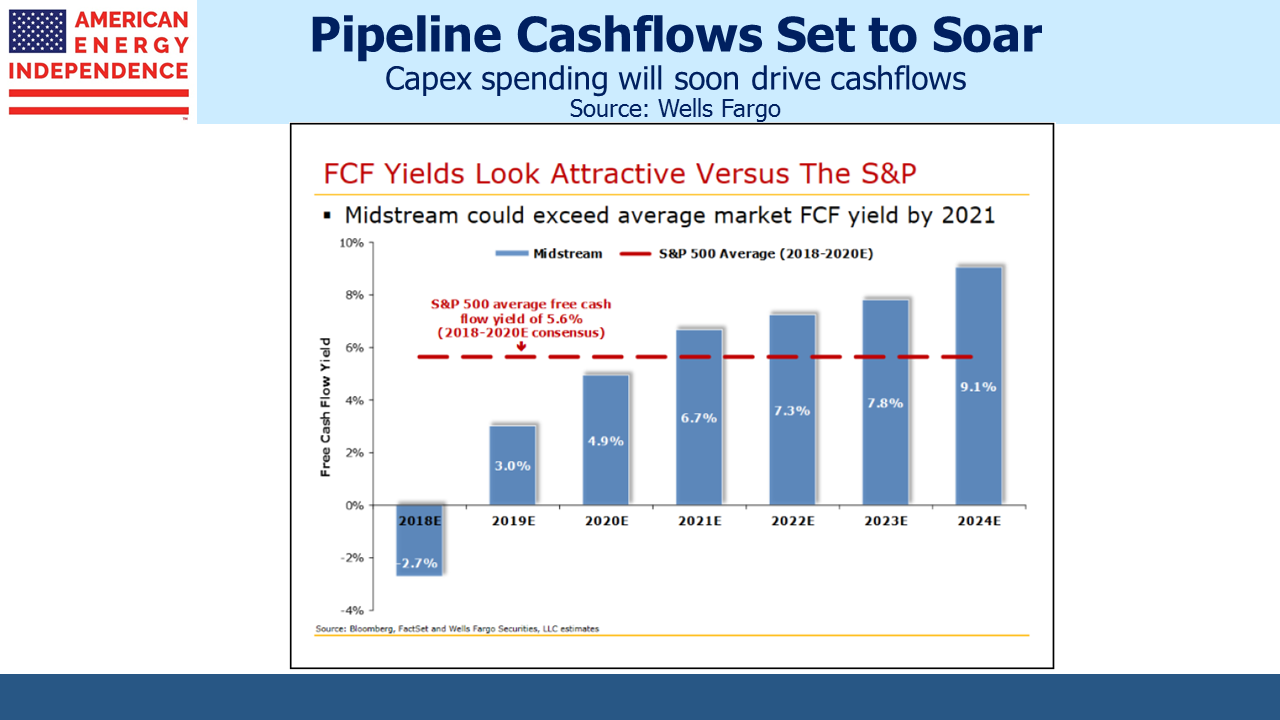

DCF yields of 10-14%or more (as with ET’s 16%) are dramatically higher than FCF yields of 3%, because DCF measures cash generated before funding for growth projects while FCF is after.FCF yields are set to rise sharply over the next few years, but this crucially relies on new investment coming down. The industry has a habit of showing that peak spending on new projects is imminent, only to push that back another year. 3Q earnings calls saw 2019 estimated capex creep up by almost 20%.

2018 is the fourth year of distribution cuts for MLPs, as reflected in the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP). Corporations have fared better, and next year we expect dividends on the American Energy Independence Index to grow by 8-9%. If midstream companies are as financially disciplined as they claim, they’ll follow the advice from Wells Fargo in evaluating stock buybacks alongside new investments under consideration. It would complete their metamorphosis into more conventional companies.

Disclosure: We are invested in ET and SEMG. We are short AMLP.