Which Hedge Funds Are Making A Killing As Yields Collapse

There's no question that, when it comes to analyzing massive droves of data at lightning speeds, computers are far superior to humans. But when it comes to other deeply complicated skills like, say, composing a symphony or penning a critical essay, humans have the upper hand. Why? Because these tasks require higher levels of judgment and reasoning that computers have yet to master.

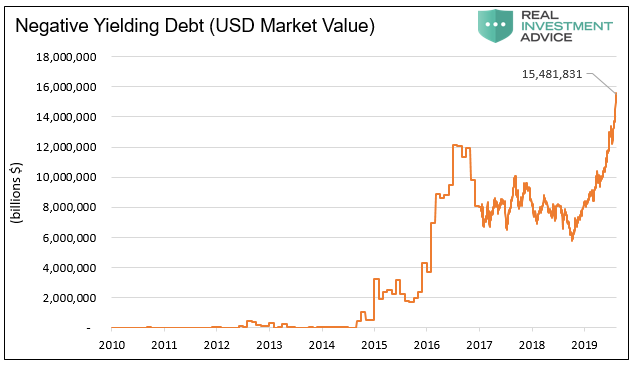

Yet, this could explain why quant funds have performed so well during the epic global bond rally that has dragged yields on $15 trillion in global debt into negative territory this year, virtually eliminating the concept of 'high yield' debt in Europe. Most recently, it sent the yield on the 30-year bund to a record low and allowed Sweden to sell 10-year sovereign debt with an average yield of minus 0.295%, joining an elite group of issuers who have sold debt priced in such a way that buyers who opt to hold it to maturity will face a certain loss.

For humans, particularly for those who lack the luxury of a Phd in economics, it might seem bizarre to ask a lender to pay a borrower for the privilege of borrowing the lender's money. Computers, on the other hand, are totally unfazed by this concept. They're much better at buying when the model says to buy, and selling when it says to sell.

As the FT reports, several quant funds have ridden the epic bond rally to market-beating returns while long-short equity peers are still struggling to time the market.

So far this year, managers who held on to their bonds as yields plunged to zero, and below, have reaped some of the biggest profits. We even pointed out that those who bought this 100Y Austrian government bond in the secondary market this week would receive half of their money back in 2117 when the bond matures. Then again, they'd also be dead.

If you buy the Austrian 100Y bond today at 200 cents, at maturity in 2117 you will get half your money back. You will also be dead pic.twitter.com/ynmKhN9WOW

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 15, 2019

Which is why it's so imperative that they find a bigger fool to take the bonds off their hands some time between now and then - and preferably at a higher price.

In the report, the Financial Times, names a few quant funds who have put up huge numbers thanks to their bets on falling yields.

Among the biggest winners are computer-driven hedge funds that try to latch on to market trends. While many human traders may question the wisdom of buying or keeping a bond that apparently offers a guaranteed loss, robot traders that monitor price moves have no such qualms.

GAM Systematic’s Cantab Quantitative fund has gained 36.1 per cent, according to numbers sent to investors, with the biggest gains coming from bets on falling bond yields.

Stockholm-based Lynx Asset Management’s main fund is up 20.7 per cent while a smaller, more leveraged fund it manages has gained 30.6 per cent, according to numbers sent to investors. Lynx has been running close to the maximum bet it is permitted on falling bond yields, said a person familiar with its positioning.

Meanwhile, Winton Group, one of the world’s biggest hedge funds with around $20bn in assets, has gained 3.5 per cent in its flagship fund this year, helped by bets on futures on German and Japanese bonds.

Meanwhile, human traders who haven't been able to ignore the fundamentals - or at least anyone who is still foolish enough to believe that fundamentals like GDP and real interest rates have any bearing whatsoever on markets that have long been beholden to the excesses of central bankers - haven't fared so well.

Those who have "focused on fundamentals have struggled to hold on to bonds" as yields have turned negative, said Anthony Lawler, head of GAM Systematic.

To be sure, some human traders have managed to figure out that it's all about the momentum.

Nevertheless, some high-profile human traders have done well from the fixed-income frenzy this year. Brevan Howard, headed by billionaire Alan Howard, has gained around 8.5 per cent in its main fund, while Caxton Associates is up 16.3 per cent and Greg Coffey’s Kirkoswald Capital Partners is up around 18 per cent, all helped by bets on falling yields.

"Looking at negative yields can be a bit misleading," said Emiel van den Heiligenberg, head of asset allocation at Legal & General Investment Management. "There are ways of making money from it."

How, exactly? By selling the bonds to a greater fool (it's been working pretty well so far).

For example, some have been buying up 'high yield' European corporate debt and hoping the spread to two-year bund narrows. As a growing share of European corporate debt enters negative yielding territory, there are many credit-fund managers who are hoping they can ride this tend at least a little bit further.

Some negatively-yielding corporate bonds also offer value, according to some investors. Take US chemicals company Huntsman. Its euro-denominated two-year high-yield bond trades with a yield to maturity of 0.4 per cent, although its so-called "yield-to-call" -the income investors earn if the company exercises its right to repay the bonds early - is minus 0.35 per cent. Even then, that is still some distance above two-year Bunds, the benchmark safe asset, at minus 0.88%.

Fraser Lundie, head of credit at Hermes Investment Management, holds the Huntsman bond and said he would profit if the gap between the bond’s yield and Bund yields narrows. "You could create an argument that the bond is screamingly cheap," he said.

For euro-based fund managers sizing up how to bet on negative-yielding debt, the cold reality is that they are penalised for doing nothing. That is because of the negative rate of interest paid on cash held by custodians - the companies like State Street and BNY Mellon that look after a fund’s assets. That could amount to a drag of about minus 1 per cent a year, meaning that buying a bond with a smaller negative yield is more attractive than leaving cash in its account.

"Even an investment in Huntsman 2021 bonds, which are slightly negatively yielding, is an enhancement on the starting point of cash,"said Hermes’s Mr Lundie.

And finally, there's the good old-fashioned carry trade.

For starters, fund managers based outside the eurozone can profit from buying Europe’s negative-yielding government debt thanks to an uplift from hedging the currency. That is because such hedges are based on the relative levels of short-term interest rates. These are much higher in the US than in the euro zone, meaning dollar-based investors are effectively paid to hedge their euro exposure back into dollars.

For instance, a two-year German Bund currently yields around minus 0.88 per cent. However, after hedging the currency, this becomes a positive yield of around 1.9 per cent for dollar-based investors. For a US-based investor, this is better than buying a two-year Treasury.

But for how much longer can this game of musical chairs continue before demand disappears and a dramatic repricing occurs. We caught a glimpse of what this might look like in Argentina on Monday (take a look at the century bond and remember this a country that has defaulted eight times).

Though at least Europe and the US have their respective central banks to backstop their markets...but at what point do we risk accidentally drifting into MMT territory.

Disclosure: Copyright ©2009-2019 ZeroHedge.com/ABC Media, LTD; All Rights Reserved. Zero Hedge is intended for Mature Audiences. Familiarize yourself with our legal and use policies every ...

more