The Market Week In Review - Friday, May 8

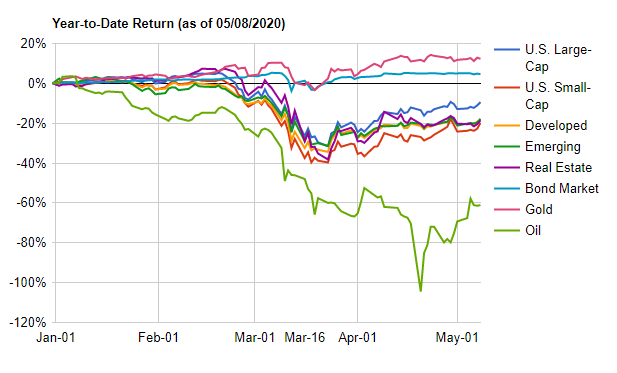

The U.S. stock market finished the week higher despite record-breaking unemployment numbers as some states begin the early phases of reopening their economies. Interest rates moved higher on the longer end of the curve as the 10-year treasury yield rose from 0.64% to 0.69%, but moved lower on the shorter end with the 2-year treasury falling from 0.20% to 0.16%. The price of gold was little changed on the week, rising only $2 to $1,709 an ounce. The price of crude oil continues to rise higher after dipping below $0 a barrel on April 20th as it finds support from production declines and improving demand.

(Click on image to enlarge)

The Worst Jobs Report Ever?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported this morning that a record 20.5 million American jobs were lost in April, while the unemployment rate soared to 14.7%. April’s job losses follow a steep decline in March as well when employers cut 870,000 jobs. The job numbers are so gloomy that some commentators suggest that we are in the midst of the worst labor market crisis ever. I say, far from it. That “distinction” unquestionably belongs to The Great Depression.

The job losses brought on by efforts to curtail the spread of Covid-19 greatly surpass the 8.7 million jobs lost during the 2008-2009 recession, when the unemployment rate peaked at 10% in October of 2009. The only time the employment rate has been higher than now was during the height of the Great Depression, when it is estimated that the unemployment rate peaked at about 25%, in 1933.

However, there is one huge difference between the Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the current unemployment crisis. In the first two instances, the job losses were triggered by a deep-rooted economic crisis, whereas in the present case the trigger is medical, and the job losses were brought on by a temporary policy decision.

Before the Coronavirus necessitated strict social distancing rules, the U.S. economy was firing on all cylinders, and employment was at an all-time low. Compare that with the Great Depression, when

- Unemployment averaged 18% for ten years.

- A series of bank runs led to tens of thousands of banks closing their doors.

- GDP was cut in half, in part due to deflation. (Inflation-adjusted GDP fell by over 25%.)

- The Consumer Price Index fell 27%.

- World trade plummeted by 26%.

Undoubtedly, April was one of the worst months in U.S. history for workers. That said, the sharp rise in unemployment resulted mainly from temporary, not permanent, layoffs. How long the current employment crisis lasts will depend primarily on (i) how quickly a treatment and vaccine can be developed, (ii) how smoothly the economy reopens, and (iii) whether reopening the economy too soon leads to a second surge in cases.No one can answer these questions with a high degree of certainty, but at least news from the medical front has been encouraging as of late.

The recent stock market rally suggests that many investors are already betting that the worst of the pandemic is behind us. I am not so sure, which is why I encouraged my clients to use the recent rally as an opportunity to lessen their exposure to stocks. I discuss these thoughts in this week’s podcast, which you can find here.

One thing I do feel confident about is that things will not get as bad as they were during the Great Depression. Far from it. Sensational comparisons of the current crisis to the Great Depression may make for good headlines, but they are not only unjustified, they are a threat to our country’s morale.

Should You Worry About Your Muni Bond Investments?

Municipal bonds have had a rough ride lately, raising questions about the safety of these securities. Aren’t munis supposed to be as safe as Treasuries? Actually, no—not quite.

No paper investment compares with Treasuries, which enjoy the backing of the world’s reserve currency. U.S.-based munis come close, or at least some of them do. In particular: many investment-grade general obligation munis are backed by the taxing power and credit quality of the issuing entity. So-called revenue munis, which are supported by a specific project – a toll bridge, for instance – are a different animal and may carry additional risk.

Yet even a slightly higher risk over Treasuries has turned into a major headache for the muni market recently. The economic and health crisis triggered by Covid-19 has created trouble for a number of state and local governments in the form of revenue shortfall and, in some cases, dramatically higher spending demands.

History suggests muni risk is extremely low, particularly for a diversified portfolio of the securities. The default rate for investment-grade municipal bonds was just 0.18% for 1970 through 2016, according to Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board. That’s higher than zero for Treasuries, but it’s ten times lower vs. investment-grade corporates.

It wouldn’t be surprising to see the muni default rate edge up in the next year or two. But relatively low risk generally for muni bonds, combined with the federal government’s backstop support that was announced recently, suggest that this corner of the market will remain the safest after Treasuries.

Negative real yields and asset allocation

Treasury yields have turned negative recently—again. It’s not the first time that the inflation-adjusted interest rate on U.S. government bonds has slipped below zero. What’s different this time: the catalyst is falling yields rather than rising inflation, at least so far.

(Click on image to enlarge)

The implications for portfolio strategy present a familiar challenge. The only way to generate a positive real return via Treasuries: embrace more risk, either by allocating more to risk assets (such as stocks) or chasing higher yields via longer maturities and lower-grade bonds.

But with so much economic uncertainty at the moment, it’s premature to rush into higher risk allocations until there’s more clarity on how and when the economy rebounds.

What’s the timing outlook for a vaccine?

The world may never return to the pre-crisis era, but the Covid-19 crisis will fade once a vaccine is developed and distributed. When should we expect one?

A “typical” development period can last five to ten years, and even then success is far from guaranteed, notes a recent report from Bruguel, an economics-focused think tank in Brussels.

If you’re inclined to think on the bright side, the Ebola epidemic is encouraging: a vaccine flew through the first three phases of clinical trials in just ten months – dramatically faster than the seven to eight years that’s typical.

Will development of a Covid-19 vaccine move as swiftly? Unclear. The good news is that research is feverishly unfolding at many companies and university research divisions around the world.

Nonetheless, an estimate that’s optimistic and realistic points to sometime next year as the best-case scenario at this point.

“I don’t think that the general population will have vaccine probably until the second half of 2021,” predicts Marie-Paule Kieny, research director at Inserm, the counterpart in France to the National Institutes of Health in the U.S. “And that’s if everything works OK”.