Mortgage Rate Decline Slowed By New Fee Charged By Fannie Mae And Freddie Mac

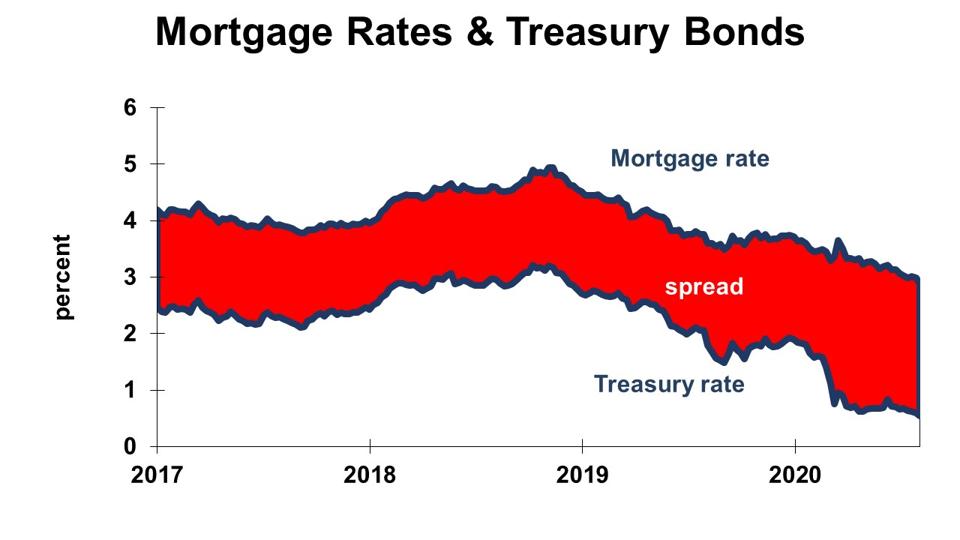

The interest rate on mortgages has not fallen as much as the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds

DR. BILL CONERLY BASED ON DATA FROM FEDERAL RESERVE AND FREDDIE MAC

Mortgage refinance costs swung up due to a new fee, which some are calling a tax. The eventual path to lower rates (which I recently predicted) will be slowed, but not entirely stopped. The announcements by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac say the lump-sum fee of one-half a percent of the loan balance applies to refinances on single family homes. It does not apply to construction loans converting to permanent loans nor to mortgages for home purchase.

Fannie and Freddie are government-sponsored enterprises, which is a little confusing in itself. They are enterprises, meaning they have profit and loss statements. But they are government-sponsored, so their debt is treated kind-of-like government debt. They can pay lower interest rates than private companies would have to pay. With that advantage, they have near-total control of the market for mortgages that conform to their guidelines.

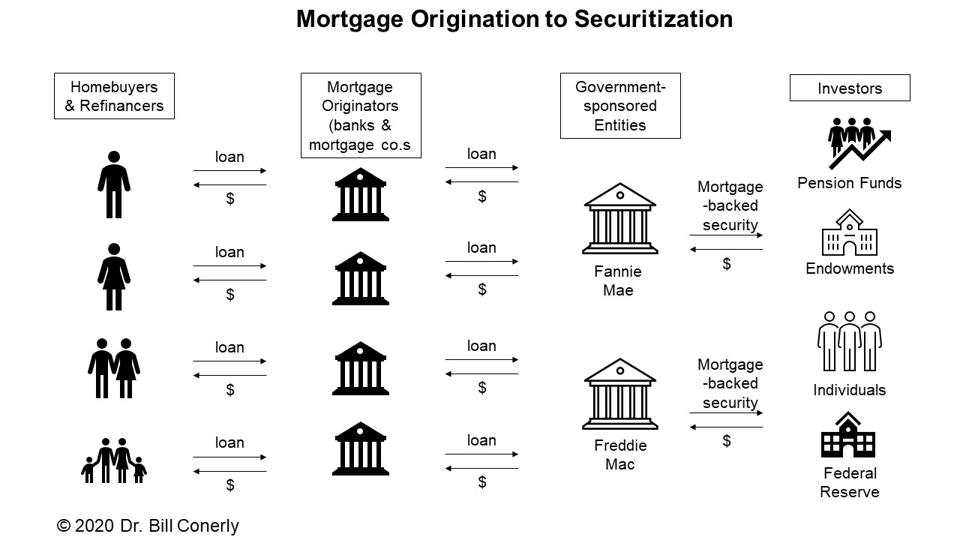

Interest rates on 30-year mortgages usually run at a steady premium over the interest rates on 10-year Treasury bonds. But early in 2020, the Treasury rate plummeted without mortgage rates following along fully. This wider margin was explored in William Emmons’ article, “Why Haven’t Mortgage Rates Fallen Further.” Most mortgages that conform to Fannie and Freddie’s loan guidelines are bundled in groups and sold as mortgage-backed securities. The process creates two spreads. At the retail level, the interest rate charged to borrowers is higher than the interest rate paid to owners of the mortgage-backed securities. The mortgage originator—a bank or independent mortgage company—pockets the difference to cover their costs and to earn a profit. The second spread is called the wholesale margin: the difference between the interest rate earned on mortgage-backed securities and what government bonds are paying.

The mortgage process from origination through securitization DR. BILL CONERLY

Emmons’ analysis of data from the spring of 2020 found that most of the wider margin of retail mortgage rates over treasury bond yields was due to retail spread. Emmons confirmed to me by email that more recent data continue that pattern. Basically, the company that the homeowner goes to for a refi is pocketing higher revenue. A portion of the higher revenue covers higher costs of operating during the pandemic, but most of the revenue flows through to profits.

The new fee is Fannie’s and Freddie’s attempt to capture some of the profits to build up their reserves. The immediate effect was that mortgage rates jumped up, perhaps out of anger or irritation by mortgage processors.

To determine the effect of the fee on the mortgage rate that a typical refi customer is quoted, we begin with basic supply and demand. In a typical textbook example, an increase in costs through a tax or necessary fee is usually passed through, partially, to customers. Some of the tax cannot be passed through, so it lowers the seller’s profit.

However, this would not be the case if capacity was limited. Sometimes a seller cannot expand supply, at least not as fast a demand is growing. That is the situation now. The demand for refis grew hugely when interest rates dropped, and the mortgage industry could not expand fast enough. Mortgage companies and banks could have turned customers away, but instead they raised their profit margin.

In such a case, the tax would be borne entirely by the sellers and not at all by the consumers. If the mortgage companies bumped up their rates to cover the cost of the new fee, some customers would decide not to refinance. Mortgage companies would have unused capacity, and some would cut rates to bring customers back in. Competition among sellers would bring the price back down.

So at a point in time, this fee appears to be bad news just for mortgage industry profits and not for homeowners looking to refinance their mortgage.

However, the industry’s capacity constraint is not fixed. Indeed, the industry has been expanding as fast as it could to serve the millions of people looking to refi. The new fee will lower profits, so the mortgage industry will expand less rapidly. That will slow the decline in mortgage spreads. And spreads will never return to the lows they had previously seen, because of the higher cost. So the fee looks benign for a day or two, but not afterwards.

Mortgage rates will continue to decline from the current level, but not as fast, nor as far, as would have happened if Fannie and Freddie not chosen to add this fee.

Disclosure: None.

Fannie and Freddie previously was not sustainable and most likely will not be in the future. That is why downturns they rely on you, the taxpayer to foot their deficient cash flow. A fee is fine if this remedies this, however, I doubt it will. I also doubt the cost will not remain with the finance company. It will be passed onto you. In the end, this is why the US needs to stop supporting these and allow the market to make a system that remedies the US being the backstop for a private company. After that we can talk about TBTF banks although they got some remedies by making loans they won't hold and dumping them onto Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

If you say this doesn't seem capitalistic you would be right. If you say this seems corrupt, you would be correct. If you say this should be stopped, that is what I'm arguing. Yet it persists somewhat because it inflates housing prices which allows the government to tax you more. A unvirtuous circle indeed. This is one major reason why home prices are inflated.