A Rose By Any Other Name - Coronabonds And The Future Of The Eurozone

On April 9th the Eurogroup of Finance Ministers eventually agreed upon a three-pronged package to avert some of the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. For financial markets this was a relief, had the Eurogroup broken up, for the second time in a week without a deal, markets would have reacted badly. The three-pronged package included health expenditure funding from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), loans for businesses from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and further funding from the European Commission’s unemployment fund. The total package is a modest Euro 540bln, the political ramifications are much less so.

What was not agreed, despite the unprecedented circumstances surrounding the pandemic, was a collective pooling of Eurozone (EZU) resources in the form of ‘Eurobonds,’ deftly renamed ‘Coronabonds,’ by their advocates. For the fiscally responsible countries of Northern Europe, even the current crisis was insufficient for them to contemplate underwriting the prodigal South.

The compromise, agreed last week, included the use the ESM. The ESM itself, together with the outright monetary transactions (OMT) undertaken by the ECB, were forged in the 2010/2012 Eurozone crisis. At that time the convergence of Eurozone government bond yields, which had begun long before the advent of the Euro, was unravelling as investors realised that Europe would not collectively underwrite any individual state’s obligations. The North/South divide became a chasm, with Greek, Portuguese, Italian and Spanish bond yields rising sharply whilst German, Dutch and Finnish yields declined. The potential default of a Eurozone government was only averted by the actions of the then President of the ECB, Mario Draghi, when he stated that the central bank would do, ‘Whatever it takes.’

Once again, a motley deal has been forged, recriminations will follow. Whilst lower government financing costs remain a major attraction of EZ membership for newer members of the EU, the benefit is by no means guaranteed, as this 2017 paper - Eurozone Debt Crisis and Bond Yields Convergence: Evidence from the New EU Countries – by Minoas Koukouritakis, reveals: -

Based on the empirical results, there is some clear evidence of strong monetary policy convergence for each of the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia to Germany. Alternatively, under the UIP and ex-ante relative PPP conditions, the expected inflation rate of these three countries has converged to the expected inflation rate of Germany. This is an expected result not only because Lithuania and Slovakia are already Eurozone members, but also because Germany plays a very important role in the economies of these three countries. Furthermore, the empirical results provide evidence of weak monetary policy convergence for each of Croatia and Romania to Germany. In contrast, for the remaining seven new EU countries, namely Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Latvia, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, the empirical evidence suggests yields’ divergence for each of these countries in relation to Germany. For Cyprus, Latvia and Slovenia, which as Eurozone members they have common monetary policy with Germany, the empirical evidence could probably be attributed to the increased sovereign default risk of these countries, which in turn led to large and persistent risk premia.

In summary, the empirical evidence indicates that in the context of the Eurozone debt crisis, even though Germany has established its dominance and sets the macroeconomic policies in the Eurozone, several new EU countries are unable to follow these policies. And this conclusion addresses once more the issue of core-periphery in the Eurozone and, thus, the Eurozone’s future prospects.

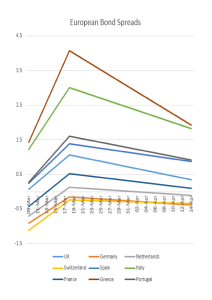

The past six weeks has seen a global fiscal response to the pandemic. Stock markets have declined and credit spreads in corporate bond markets have widened. In European government bonds the pattern has been similar, the migratory flight to quality saw flocks of investors head north, especially into Switzerland and Germany. The simplified chart below shows three data points;

March 9th, when German Bund yields reached their recent nadir,

March 18th, the date investors became spooked by the sheer magnitude of the fiscal response required by EZ governments: and

April 14th, the day on which Italy and Spain announced the first relaxation their lockdown restrictions: -

Source: Trading Economics, Investing.com

There are several observations; firstly, even as the lockdown comes towards its end, bond yields are higher, reflecting concerns about the impact of fiscal spending on government budgets as tax receipts collapse. Secondly, German Bund yields are now lower than Swiss Confederation bonds, despite expectations that Germany may end up footing the bill for the lion’s share of government borrowing across the EZ. This may be a reflection of the lower percentage fatality rate in Germany – 2.5% versus 4.4% in Switzerland – or simply a function of the greater liquidity available in the German bond market.

A third observation concerns the higher yielding countries of Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Despite a larger number of Covid-19 infections, Spanish Bonos have maintained their lower yield relative to Italian BTPs, meanwhile, Greek bonds have converged towards Italy and Portuguese bonds trade within 4bp of Spain.

Convergence, divergence and political will

This is not the first macro letter on the topic of EZ bond convergence, the chart below is taken from Macro Letter – No 10 – 25-04-2014 - The Limits Of Convergence - Eurozone Bond Yield Compression Cracks the second of eight previous articles on subject: -

Source: Bloomberg

At that time I suggested three scenarios: -

- Full Banking Union and further federalization of Europe

- Full Banking Union but limitation of federalization

- Eurozone break-up

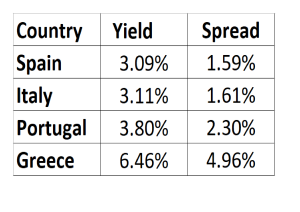

The EZ crisis had finally disapated but the full impact of QE had not yet been appreciated, the table below shows the yield to maturity and spread over German Bunds of the 10 year bonds of Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal traded on 24th April 2014 (roughly six years ago): -

Source: Bloomberg

In April 2014 I saw the second scenario as most likely. I anticipated limited ‘Eurobond’ issuance, this has not yet come to pass, but last week’s stimulus looks like a federal bail-out by any other name. Last month, as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold, the spread between German Bunds and Spanish Bonos touched 1.54%, whilst the spread against Greek bonds reached 4.22% and Portugal, 1.75%. Only Italy fared less well, the Bund/BTP spread reached 3.15; a marked deterioration since 2014.

Conclusions and Investment Opportunities

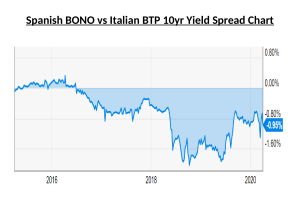

By the time I penned Macro Letter – No 73 – 24-03-2017 - Can a multi-speed European Union evolve? it was becoming clear that Italy was the focus of concern among fixed income investors. I concluded (a little too late) that: -

Spanish 10yr Bonos represents a better prospect than Italian 10yr BTPs, but one would have to endure negative carry to set up this spread trade: look for opportunities if the spread narrows towards zero.

The spread never returned to parity.

When I last wrote about EZ bonds, I focussed once again on Italy in Macro Letter – No 98 – 08-06-2018 - Italy and the repricing of European government debt. BTP yields had risen to a spread of 1.22% over Spanish Bonos and I expected a retracement. As the chart below reveals, BTP yields rose further before than regained composure: -

Source: Y-Charts

Eurobonds are still not on the agenda even in a time of pandemic, therefore, Italian indebtedness remains the single greatest risk to the stability of the EZ. The convergence trade is fraught with geopolitical risk as cracks in the European Project are patched and papered over. Now is not the time for revolution, but the ongoing fiscal strain of the pandemic means the policy of issuing Eurobonds backed by a European guarantor will not go away. I expect EZ government bond yield compression accompanied by occasional violent reversals to become the pattern during the next few years, together with increasing political tension between European countries north and south.