A Tale Of Two Surplus Countries: China And Germany

Today we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Yin-Wong Cheung (City University of Hong Kong), Sven Steinkamp (Universität Osnabrück) and Frank Westermann (Universität Osnabrück). This contribution is based on a paper forthcoming in the Open Economies Review.

In recent years, large and sustained current account imbalances have been a focus of research in international economics. While there is a large literature on deficits and their economic implications, there is only limited research on large and sustained surpluses (Edwards, 2004). This is surprising in the light of a longstanding concern, for instance stressed by Keynes (1941) and Kaldor (1980), about the role of surplus countries in international adjustments. More recently, Christine Lagarde, the IMF’s managing director, aptly pointed out the link between deficits and surpluses when she said: “It takes two to tango.” The deficits of some countries are matched by surpluses in others, and it is important to understand both phenomena.

China and Germany are two prime examples of net exporters that have experienced large and sustained surpluses over the past 20 years; in 2015, they accounted for 42% of the world’s total surplus. They are unparalleled in their current account surpluses, even compared to other stereotype surplus economies, such as Japan, Korea, and Switzerland.

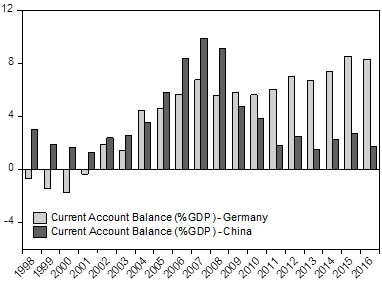

Figure 1: Current Account Balances – China vs. Germany

In a new research paper (Cheung et al. 2019, or view-only share version), we update and extend the comparison of China and Germany (Aizenman and Sengupta, 2011). We illustrate that, during the post-global financial crisis (GFC) period, the two countries have displayed dis-similar current account behaviors (Figure 1). While both countries have been running current account surpluses for most years over the past two decades, China’s surplus has started to shrink after the GFC. Germany’s current account surplus has, in contrast, stayed at a high level and even experienced a steady increase. Apparently, the current account balances of these two surplus countries exhibit a similar pattern before the GFC but have moved in different directions thereafter.

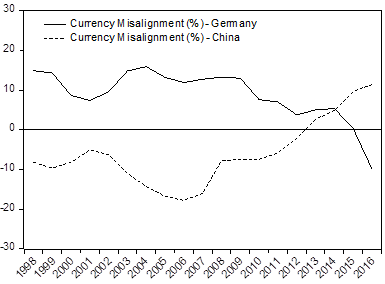

It is commonly believed that China has maintained an undervalued exchange rate, whereas Germany has an overvalued one. Figure 2, however, shows that in recent years, the valuations of these two currencies move in opposite directions according to the Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII). Specifically, these currency misalignment estimates show that the Chinese level of misalignment has been diminishing noticeably since 2007. Since 2012, the Chinese currency is better characterized as being overvalued than undervalued (Almås et al., 2017; Cheung et al., 2017).

In Germany, the reverse pattern holds. Since the implementation of labor market reforms (“Agenda 2010”) in the early 2000s, Germany has considerably improved its competitive position vis-à-vis its trading partners, in particular within the euro area. The currency’s degree of overvaluation has been declining accordingly and, finally, turned to an undervaluation in 2015. Visually, these currency misalignment and current account balance movements are in line with the conventional wisdom that these two variables are inversely related.

Figure 2: Currency Misalignment

Against this backdrop, we estimate the current account equations for both countries and assess the similarities and differences of the Chinese and German behaviors. We find that both countries, currency misalignment plays a significant role in determining the current account balance. While for Germany, the effect is present over the whole sample period, we find that for China it became important after the global financial crisis of 2007/8. The qualitative results on the currency misalignment effect, the post-crisis impact, as well as on other control variables taken from the literature, are robust to the choice of alternative measures of currency misalignment, the inclusion of different sets of control variables, and a seemingly unrelated regression specification. Our empirical findings buttress the negative correlation pattern observed from Figures 1 and 2.

The currency misalignment variable together with selected canonical economic factors, monetary factors, global factors, and country-specific factors can explain over 90% of variations in the current account balances of these two countries. The empirical knowledge of the underlying determinants implies that policy makers – should they decide to steer the current account in either direction – have the information and power to do so.

Is China the new Germany? One could say that China is evolving towards the “old” Germany that was an overvalued exporter experiencing a moderate surplus. Germany, on the other hand, is becoming a country with increasing surpluses, both within the euro area and with respect to the rest of the world, with an undervalued exchange rate. In both cases, the surplus can be attributed to currency misalignment and other economic factors.

Disclosure: None.