Assessing The Damage After Monday’s Sharp Decline In Stocks

Well, that was painful. The increasingly hazy risk outlook linked to the coronavirus outbreak inspired a 3.35% haircut in the US stock market (S&P 500). The tumble was certainly a bracing counterpoint to the idea that sunny optimism is the only game in town. But before we let recency bias flip to the opposite extreme, let’s review where we stand after yesterday’s smackdown.

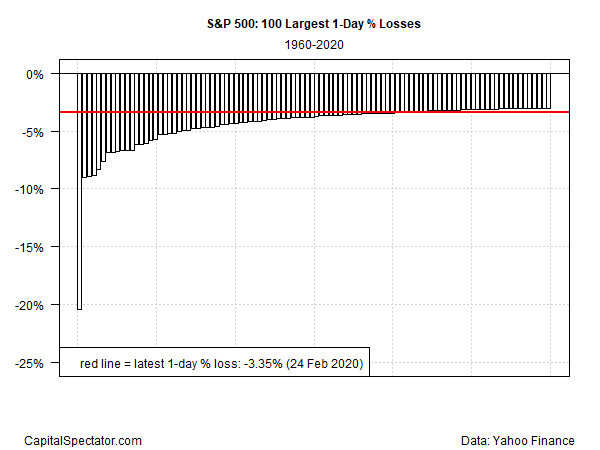

Yesterday’s decline was dramatic, but was it unusual? The answer depends on how you line up the numbers. In terms of all daily losses for the S&P since 1960, Monday’s 3.35% drop ranks as roughly in the category of the worst percentile declines. To put this another way, of the 7,000-plus days that suffered a daily loss over the past six decades, only 70 of those declines were deeper—the biggest: the 20.5% single-day crash in the October 1987.

When we contain the analysis to the 100-deepest daily declines, however, the 3.35% setback looks middling.

Another way to contextualize Monday’s decline is by viewing market activity through the lens of drawdown. The current peak-to-trough decline in the wake of Monday’s slide is roughly -4.7%, which is slightly deeper than most of the deepest setbacks in recent history but still nowhere near the darkest days of recent vintage.

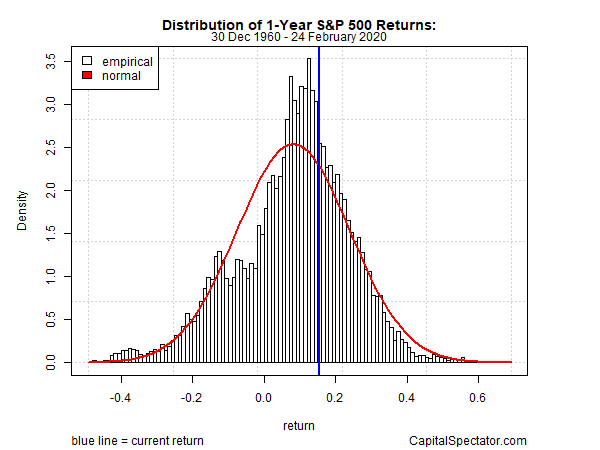

Let’s also recognize that even after the latest selloff, the S&P 500 continues to post high trailing returns relative to the long-run historical record. Since 1960, the S&P has returned a roughly 6.9% annualized total return. By that standard, the 15.5% one-year gain (based on 252 trading days) through yesterday’s close still ranks as impressive.

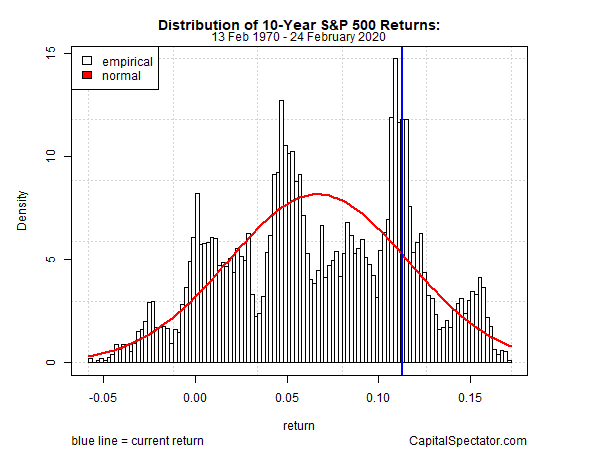

The current 11.3% annualized 10-year annualized return looks even stronger vs. history.

The question, as always, is what should we expect going forward? Yesterday’s haircut serves as a reminder that the crowd demands a bigger discount rate for stocks these to reflect coronavirus risk. There’s a lot of uncertainty about how this risk will impact the global economy, but it’s clear that the US market has been too optimistic in assessing the potential threat to the economy, in America and around the world. Yesterday’s decline is the first installment in updating the outlook.

In fact, there’s been a case for managing US equity return expectations down for some time—even before the coronavirus outbreak roiled sentiment. At the end 2019, for example, CapitalSpectator.com’s estimate of the US equity market’s long-run risk premium was roughly 5%-to-6%. Add in a generous one-percentage point risk-free rate and that lifts the outlook to, perhaps, 7% a year – far below the trailing 11.3% annualized rise over the past decade.

Rest assured that the crowd’s revised discounting efforts are still in the early stages. Where this is headed is anyone’s guess. When faced with a larger-than-usual risk factor that’s difficult/impossible to model, it takes time for the market to process the known and unknown unknowns. Along the way, the estimating and re-estimating process is prone to be messy.

“The much larger downside risk is that this continues to be a problem,” advises the former Bundesbank president tells Bloomberg.

The main mystery for investors is second-guessing how the market will price in this risk in the weeks ahead. Suffice to say, it’s an evolving process, and prone to more than a few missteps, akin the proverb of the blind men trying to “see” the elephant.

Disclosure: None.